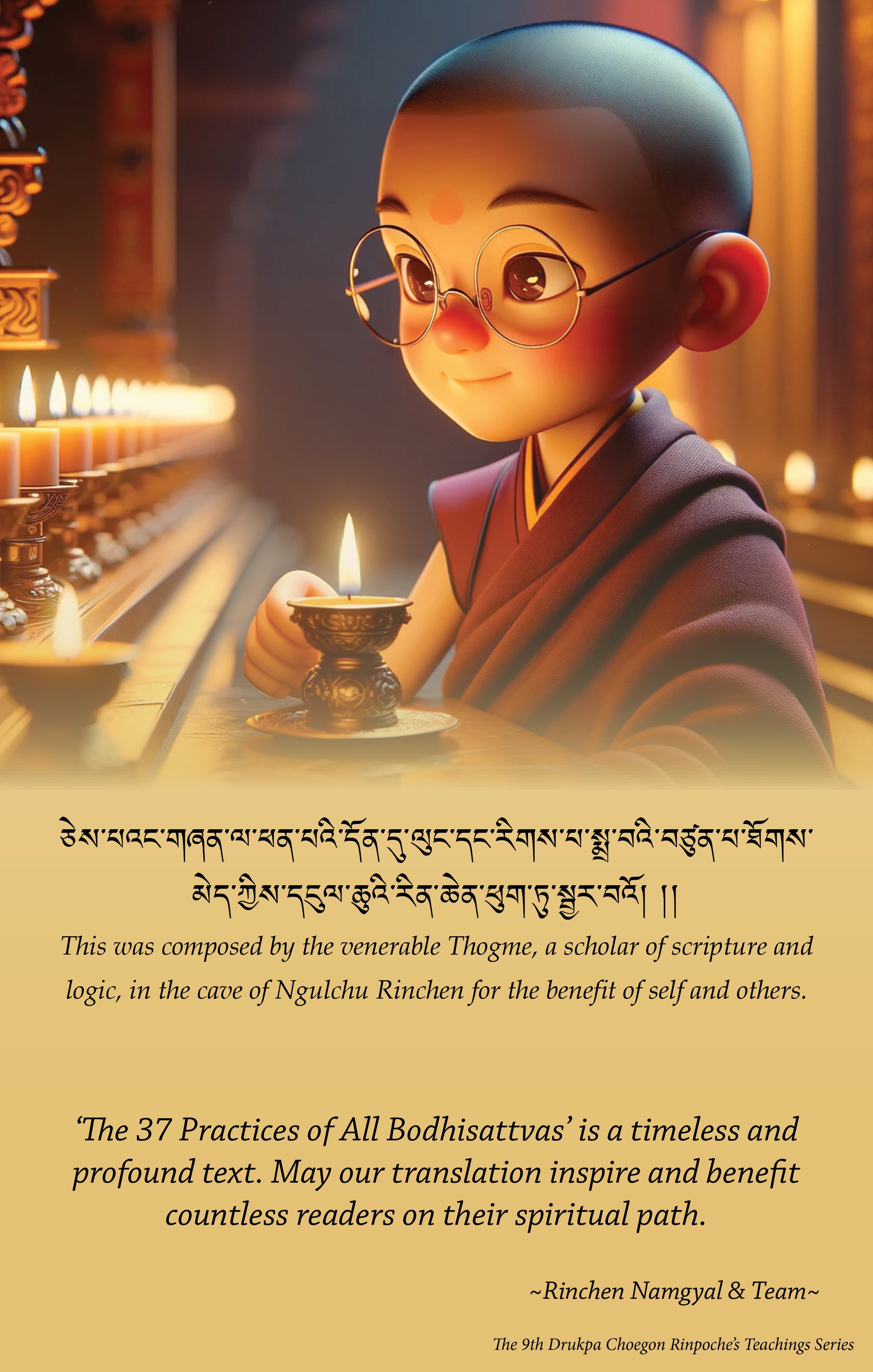

Thogme Zangpo’s Instructions -

The 37 Practices of All Bodhisattvas

The Only Path to Buddhahood

To help countless sentient beings, as boundless as the sky, liberating them from the cycle of suffering, we must first generate the supreme bodhicitta and transform our mindset. The teachings we shall explore today delineate the path that all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas must tread - the Bodhisattva Path. Gyalse Thogme Zangpo, the author, distilled the practices of all Bodhisattvas into thirty-seven succinct verses, known as the 'Thirty-Seven Verses on the Practice of Bodhisattvas.' This profound wisdom will be the focus of our study today.

What kind of text is this? Generally speaking, the Buddhas of the three times — past, present, and future — all the Buddhas of the past, all the present Buddhas existing in various realms, and all the Buddhas yet to come in the future; they have only one path to follow and practice — the sublime Bodhisattva Path. "The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas" outlines this sole path to Buddhahood. Without following this path, the perfect realization of Buddhahood is unattainable. For the Bodhisattvas presently on the path (the stages of the bhumis), the essence of their practices is encapsulated within this text. In summary, samsara and nirvana, as well as the present and ultimate peace, happiness, and all virtuous qualities, originate from this path. "The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas" is precisely such a text.

When studying, it's important not just to memorize the words but to truly grasp the underlying meaning and keep it close to our hearts. Sometimes we may be confused by words, but if we truly understand their inner meaning, we'll be able to comprehend the Bodhisattva's way of adopting and rejecting and gain insight into what actions to take and what to avoid. With this, we can unlock the essence of the thirty-seven verses and put the teachings of the Bodhisattva path into practice.

THE THREE COMPONENTS OF A BUDDHIST TEXT

All Buddhist texts follow a common structure, consisting of three sections: "The Introduction," referred to as "The Goodness of the Beginning," "The Main Body," known as "The Goodness of the Middle," and "The Conclusion," referred to as "The Goodness of the End."

"The Goodness of the Beginning" includes the title of the text, the salutation section, which expresses homage during translation, and the establishment of the intent. These three elements serve as the initial part of the text and are not considered the main content.

The Goodness of the Beginning:

-

The title allows readers to understand the content and purpose of the text at a glance, including whether it is exoteric or esoteric, and the content’s main direction. For instance, imagine having numerous medicines in our room without labels; it would be challenging to determine their specific purposes. Similarly, in Buddhism, there are 84,000 Dharmas expounded to counteract our 84,000 afflictions. These afflictions can be grouped into 21,000 types of greed, 21,000 types of anger, 21,000 types of ignorance, and an additional 21,000 types from the combination of greed, anger, and ignorance, adding up to a total of 84,000 afflictions.

The wise and compassionate masters have assigned names to these Dharmas, making it easier for practitioners to recognize which affliction each Dharma primarily addresses. This process is akin to labeling medicines, enabling practitioners to discern the purpose and function of each Dharma at a glance.

Through the tile, 'Thirty-Seven Verses on the Practice of a Bodhisattva,' we can understand that the content expounded is what all Bodhisattvas practice, outlined in thirty-seven essential points.

-

NAMO LOKESHVARA YA

Though realizing all phenomena are beyond coming and going,

Yet still you strive solely for the sake of countless beings,

Supreme guru inseparable from Avalokiteshvara,

With body, speech, and mind we prostrate at all times.

After discussing the title of the text, we move on to the salutation section. First, the phrase "NAMO LOKESHVARA YA" is in Sanskrit. "NAMO" means prostrate, " LOKESHVARA YA" refers to the Avalokiteshvara, and "YA” denotes the object.

There are several reasons for reciting the prostration verse in Sanskrit. First, it helps readers plant the seeds of opportunity to understand the Sanskrit language in the future. Second, since Buddha taught the Dharma through Sanskrit, we use the same language in our initial recitations to receive the blessings of Buddha's speech. Third, it signifies that this teaching is reliable and has valid sources, having been directly translated from Sanskrit to Tibetan, so retaining the original Sanskrit indicates its trustworthy origin.

Fourth, all Tibetan Buddhist teachings are translated from Sanskrit, and in terms of content, there is no difference between the two languages. Fifth, if the teachings had not been translated from Sanskrit to Tibetan, the Dharma would have been preserved only in Sanskrit. We can now access these teachings in Tibetan, and we should be grateful for the kindness of the translators of that time. Therefore, displaying the original Sanskrit text at the beginning is a way to express our gratitude for the translators' kindness. Based on these reasons, the Sanskrit text is used at the beginning of the text.

The first verse is a prostration verse, and the object of prostration is the guru, who is inseparable from Avalokiteshvara.

The teachings Buddha chose to expound are mainly divided into two categories: those spoken from the perspective of ultimate truth and those spoken from the perspective of conventional truth. Ultimate truth represents the actual nature of reality, the true essence, and is the manifestation of Buddha's omniscient wisdom, displaying genuine, non-deceptive, and non-illusory truth. Conventional truth refers to appearances (the way things manifest) and is the manifestation of Buddha's all-encompassing wisdom, showing deceptive and changeable phenomena. Many distinctions arise from the perspectives of ultimate and conventional truths, including definitive and provisional meanings. Ultimate truth is definitive and represents the inherent wisdom of Buddha's meditative equipoise; conventional truth is provisional and is spoken in response to ordinary beings' discriminative thoughts.

Only a guru inseparable from Avalokiteshvara can expound and express both ultimate and conventional truths.

"Though realizing all phenomena are beyond coming and going" means that the guru can perceive the essence of all phenomena. This essence is not subject to the changes of conventional truth. The guru can see it as it originally is. Although the guru can perceive the ultimate truth and abide in it, they generate great compassion within the realm of conventional truth to address the diverse needs of sentient beings. They tirelessly and diligently strive to guide all sentient beings.

A guru who possesses both ultimate and conventional truth is a supreme guru, called a "holy guru." This supreme guru is inseparable from the deity, Avalokiteshvara. We should always prostrate to the guru, who is inseparable from Avalokiteshvara, with our body, speech, and mind. This is the initial prostration verse.

When learning the Vajrayana path, we must understand that although Buddha has attained the peaceful Dharmakaya, the aspect of self-benefit, due to the power of his past aspirations for bodhicitta, he continues to manifest countless forms of rupakaya to benefit limitless sentient beings. These forms include the perfect Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya.

In order to benefit sentient beings, Buddha manifests as a wise and knowledgeable guru, especially in the era of degeneration, when beings are unable to see the Buddha directly. Thus, Buddha appears as a wise guru to guide and place his destined disciples on the path to liberation and enlightenment. The wise guru manifested through the Buddha's rupakaya is inseparable from the great compassionate Avalokiteshvara, and we constantly prostrate to this guru, who is one with Avalokiteshvara.

Therefore, the first verse is a praise, a way to make offerings to the guru and repay the guru's kindness through prostrations. The actual content is a prostration.

-

Perfect Buddhas – the source of all benefit and joy,

Arise through accomplishing the sacred Dharma,

And this, in turn, relies upon the full knowledge of their practice,

I (Thogme Zangpo) shall now explain “The Practices of all Bodhisattvas.

This verse is about establishing the intent. After reflecting on the great kindness of the guru guiding oneself onto the correct path of practice, how can one repay the guru's kindness? By generating an altruistic intention and composing this text. This is the author's mindset in establishing the intent, initiating an altruistic intention to write this text, and vowing to complete it well.

The first section of this book begins by outlining the main theme. It starts by explaining that the perfect Buddhas are the source of all benefit and joy. Our current happiness within samsara and the ultimate happiness of liberation and Buddhahood all originate from the Buddha. The Buddha is said to possess initial, intermediate, and final virtues, through which all present and ultimate happiness is accomplished.

Delving further, our happiness comes from the Buddha, but what is the origin of the Buddha? The Buddha has attained perfect Buddhahood through the correct practice of the Dharma. During the four stages of the path – the Path of Accumulation, the Path of Preparation, the Path of Seeing, and the Path of Meditation – the Buddha was even willing to sacrifice his own life for the sake of Dharma, devoting himself to the threefold training of hearing, contemplation, and meditation, in order to perfect the Methods and Wisdom of the teachings.

In terms of skillful means, explained from the perspective of Six Paramitas, it is covered by the first five practices: Generosity, Discipline, Patience, Diligence, and Meditative Concentration. These five are skillful means, while the practice of wisdom is the Prajnaparamita – the Perfection of Wisdom. Through the combination of hearing, contemplation, meditation, and the practice of both skillful means and wisdom, one can achieve the perfect state of Buddhahood. Therefore, it is said that one attains accomplishment through the practice of sacred Dharma.

How should the true Dharma be practiced? As a beginner, it is essential to understand the difference between the correct path and the mistaken path. By knowing the correct path, one can avoid falling into wrong or inverted practices. First, one should recognize the difference between the two, and then practice the Dharma accordingly. So, at the outset, those who want to learn the Bodhisattva's path should know how to practice it. That's why the author, Thogme Zangpo begins by establishing his intent to expound the correct path.

The Goodness of the Middle:

The main section of the text, known as the Goodness of the Middle, begins to unfold the thirty-seven essential points. It is further divided into preliminary practices, main practices, and concluding practices.

The preliminary practice, presented in the first seven verses, emphasizes the necessary preparations before embarking on the path of Dharma. These verses serve as a guide to lay the foundation for what lies ahead.

Transitioning to the main practice, we delve into the core teachings. This includes contemplation and cultivation of bodhicitta, the mind of enlightenment, as well as the observance of the bodhisattva vows. Additionally, it encompasses various aspects of learning and practice associated with the Bodhisattva path.

Lastly, in the concluding practice, there is a brief explanation of the paths for individuals of lower and intermediate capacities. In summary, the "37 Practices of Bodhisattvas" encompasses the content of the path for practitioners of the three levels – lower, intermediate, and advanced.

The Goodness of the Middle – I) Preliminary Practices

The journey begins with the preparation necessary for embarking on the Bodhisattva path, which is encompassed within the first seven verses. These seven verses outline the seven preliminary practices that are introduced in the main text of the Bodhisattva Path.

-

Having obtained this supreme vessel of leisure and endowment in this fortunate life,

We must strive to free ourselves and others from the ocean of samsara,

Day and night, unceasingly, without weariness or delay,

Hearing, contemplating, and meditating is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

How should we contemplate the significant rarity of attaining a human life endowed with the Eight Leisures and Ten Endowments? The first verse likens this precious human life, complete with the Eight Leisures and Ten Endowments, to a sturdy ship. This ship has the potential to carry us across the vast ocean of suffering toward the peaceful shores of a blissful pure land. This metaphor highlights the immense value and importance of our hard-to-obtain human existence.

Now that we possess this precious human life with all the necessary conditions, we have the capacity to accomplish both our own and others' benefits. Yet, we find ourselves deeply mired in the ocean of suffering. In order to attain eternal peace and to perfectly fulfill our aspirations for all virtues, we must diligently practice the Buddha's teachings. Our yearning should be as strong as that of a person who has been long starving and deeply craves food, or a person who has been long thirsty and yearns for a sip of water. Spurred by such intense desire, we must devote ourselves to the three studies of hearing, contemplating, and meditating on the Buddha's teachings, day and night, without idleness or wasting time. Only through such dedicated practice can we aspire to cross from the ocean of suffering to the other shore.

Hearing the Dharma in a human life endowed with the Eight Leisures and Ten Endowments is indeed very precious. These include the Eight Leisures and the Ten Endowments, five of which are personal endowments, and the other five are from others. Some of you may already be familiar with these, while others may not. While I won't delve into a detailed explanation here, it's important to note that no matter how extensively we discuss these leisures and endowments, it ultimately comes down to our personal understanding. The essence of Dharma is not just about listening, but it's about engaging in a continuous process of listening, contemplating, and practicing.

As Bodhisattva Maitreya taught, "We must first seek out a spiritual mentor and attentively listen to the teachings they expound. Yet, understanding should not stop at the point of hearing. We shouldn't feign understanding when we don't truly grasp the teachings, nor should we focus solely on listening without deeper contemplation." We need to question whether we might be misunderstanding something or whether our contemplation hasn't delved deep enough. This kind of self-reflection is crucial. Merely hearing and contemplating is not enough; ultimately, we must integrate these with meditative practice. As the Kadampa’s masters have warned, neglecting to practice after listening and contemplating leads us into a serious error: "The key points remain in the scriptures, the words linger on our lips, but our hearts fail to resonate with the essence of meditative practice." This is a grave mistake in our Dharma practice. Therefore, in recognizing the rarity and preciousness of human life with leisure and endowment, our earnest contemplation and inward meditation practice are of the utmost importance.

-

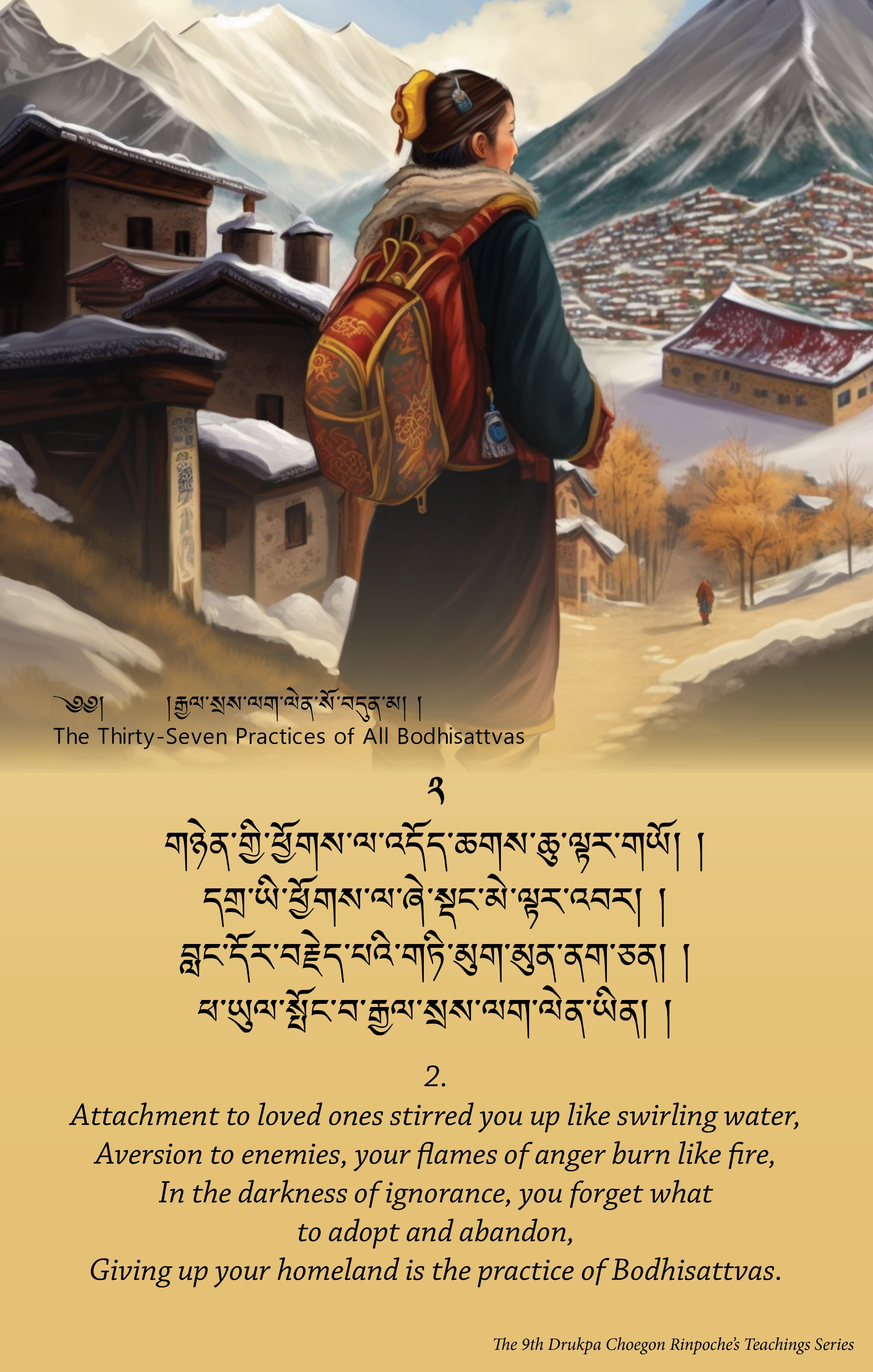

Attachment to loved ones stirred you up like swirling water,

Aversion to enemies, your flames of anger burn like fire,

In the darkness of ignorance, you forget what to adopt and abandon,

Giving up your homeland is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

Objects of affection in our hearts, often relatives and those we hold dear, can agitate our minds, much like the turbulence of boiling water. When we harbor anger or resentment towards someone, our minds can be likened to a raging fire, filled with seething fury. This illustrates the manifestations of desire and anger. Ignorance refers to our inability to distinguish what actions should be embraced and what should be avoided. So, what should we do? We need to adopt the ten virtuous actions and abandon the ten unwholesome ones. Forgetting these principles of discernment is a sign of ignorance. Furthermore, when we act without mindfully observing our actions or fail to bring ourselves back when our thoughts stray, we're in a state of mindlessness, which is also a form of ignorance.

The primary reason our minds are immersed in the darkness of desire, anger, and ignorance often lies in negative environments. These are places that lack peace, like our hometowns, where gossip and rumors run rampant. When we encounter such conditions, we need to be determined to let go, just as urgently as a person would distance themselves from the source of a contagious disease. Therefore, we must urgently abandon and step away from any environment that might fuel our greed, anger, and ignorance.

There are countless examples throughout history that reinforce the truth of this verse. Many practitioners encountered obstacles in their spiritual journey due to their attachments to family and friends. This is why the Buddha left his royal palace for a life of asceticism, ultimately attaining perfect Buddhahood. Our hometowns — places that give rise to our desires and anger — can be obstacles in our spiritual practice. Hence, historically, many monks have chosen to leave their familiar environments to seek solitude in the mountains for their spiritual practice.

Take, for example, the revered Milarepa. His love for his mother was so strong that when his aunt and uncle mistreated her, he recklessly learned and used malicious curses against his relatives, killing many and creating a lot of negative karma. All of this stemmed from his intense attachment and love for his mother. Eventually, he left his hometown and met his esteemed teacher Marpa. This encounter led to a profound realization of his negative actions, which drove him to diligently practice the Dharma.

Later, when thoughts of his hometown crossed his mind, he returned, only to find his mother had passed away and his home was deserted. At that poignant moment, he completely renounced this life and retreated to the mountains to practice earnestly and, ultimately, attained the union form of Vajradhara within his very lifetime.

These examples illustrate how our failure to let go of desire and anger can obstruct our spiritual practice, thereby reinforcing the teachings in this verse. We can learn from these accounts that detaching ourselves from such detrimental emotions is essential for our spiritual progress.

-

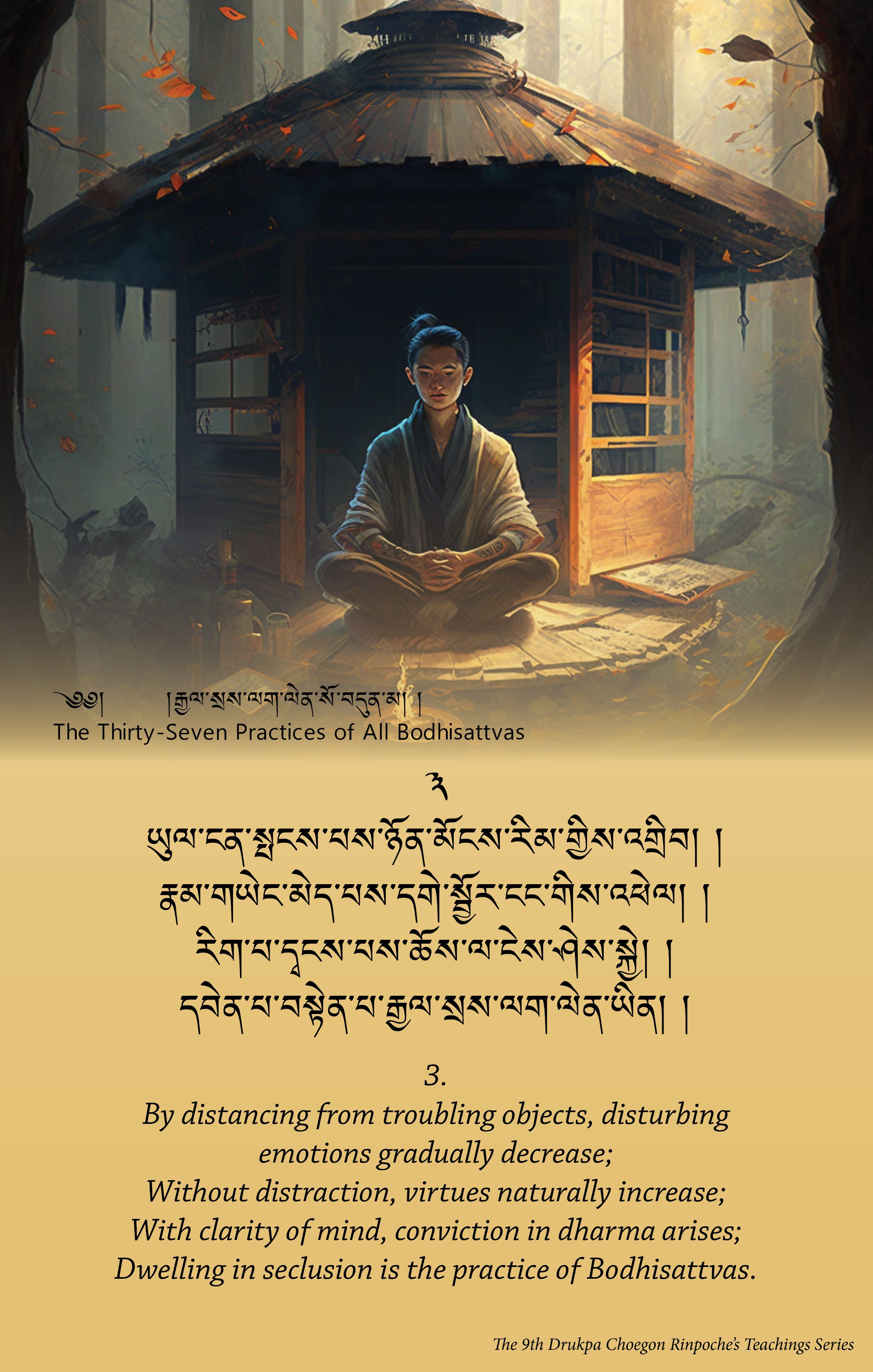

By distancing from troubling objects, disturbing emotions gradually decrease;

Without distraction, virtues naturally increase;

With clarity of mind, conviction in dharma arises;

Dwelling in seclusion is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

The previous verse discussed harmful places or environments. So, what kind of environment is beneficial to us? It's a serene and tranquil place, away from the hustle and bustle, a locale praised by both Sutrayana and Tantrayana. By anchoring ourselves in such serene surroundings, our distractions naturally fade, and our faith in the Dharma, as well as our compassion, loving-kindness, and Bodhichitta, naturally grow.

Our minds are an eternal battleground where good and evil constantly contend. In a peaceful environment, destructive emotions like greed and anger cease to proliferate unchecked. As the negativity within us recedes, virtues that stand in opposition naturally grow. When goodness dominates, evil retreats; when goodness wanes, evil escalates. Conversely, when evil prevails, goodness diminishes. By distancing ourselves from environments that nurture evil thoughts, their influence weakens, and guided by the principles of dependent origination and natural laws, various virtuous qualities within us naturally flourish.

Therefore, it's stated here that when we distance ourselves from negative places, our confusion, ignorance, and afflictions naturally lessen. Merits of goodness, such as diligence, faith, and compassion, naturally arise in our minds. Our faith in the Dharma strengthens, and our understanding of its principles and rules sharpens. Hence, serene environments are beneficial, and we should seek and rely on them.

In this verse, the emphasis is placed on the tranquility of the environment. Pertaining to practice, according to Patrul Rinpoche, tranquility encompasses the threefold tranquility of the body, speech, and mind.

Physical tranquility involves abstaining from frequently immersing ourselves in bustling, crowded environments or attending numerous gatherings and social events. Even if a retreat to the mountains for practice isn't feasible, we can still cultivate physical tranquility within the city by refraining from frequent gatherings and avoiding distracting activities.

Verbal tranquility entails avoiding the expenditure of energy on meaningless talk. At home, we can recite mantras and sutras. Even when we are not engaging in the recitation of sutras or mantras, we should abstain from pointless conversations. From the Tantric perspective, speaking is a form of karmic energy. When this energy is engaged, our inherent wisdom-energy transforms into karmic energy. Consequently, we fail to nurture our inherent wisdom-energy and to conserve our strength. To practice verbal tranquility within the city or at home, we should often observe silence, refrain from meaningless speech, and consider reciting mantras or sutras when possible. As Patrul Rinpoche taught, even if we inhabit a mountain retreat (a peaceful place), we can't accrue the merits of such a tranquil place without achieving verbal tranquility.

Mental tranquility is maintaining a mind that's continually in a state of meditative concentration, free from distractions and delusive thoughts.

The true meaning of tranquility is to distance ourselves from objects that incite greed and anger. Understanding the meaning of tranquility does not imply that we must retreat and live in the mountains. Rather, we should isolate ourselves from triggers of desire and anger within our environment, thus preventing excessive disturbances to our body, speech, and mind and enabling practice in a serene environment.

If we lack a genuine understanding of tranquility, even a mountain retreat wouldn't benefit us. We may waste much time in idle chatter, remain in a distracted state, and be swarmed by delusive thoughts. Some people may seclude themselves in the mountains, their doors shut, but their minds may be more overrun with delusive thoughts than when they resided in the city. This is due to a lack of a genuine understanding of tranquility. Therefore, it's essential to comprehend that tranquility includes physical tranquility, verbal tranquility, and mental tranquility. These three aspects should be kept in mind, and when we speak of relying on a tranquil environment, we should incorporate them into our practice.

In summary, to genuinely benefit from a peaceful environment, we must understand and incorporate the principles of tranquility into our daily lives. This means practicing physical tranquility by avoiding overly stimulating environments, verbal tranquility by refraining from meaningless chatter and focusing on reciting mantras or scriptures, and mental tranquility by maintaining a concentrated, meditative state of mind. By integrating these facets of tranquility into our practice, we'll be better equipped to cultivate our inherent wisdom, deepen our faith in the Dharma, and naturally foster our virtuous qualities.

-

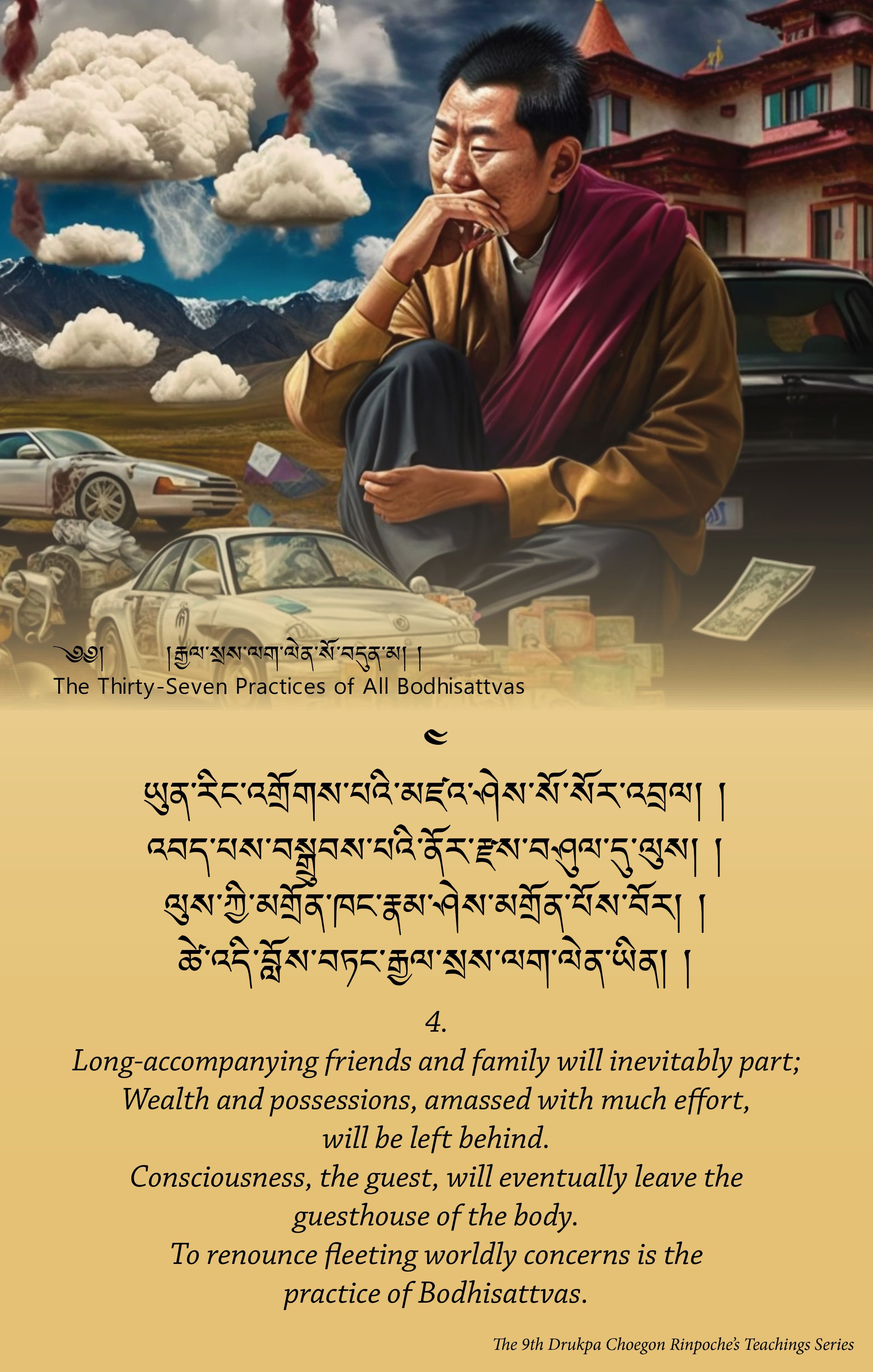

Long-accompanying friends and family will inevitably part;

Wealth and possessions, amassed with much effort, will be left behind.

Consciousness, the guest, will eventually leave the guesthouse of the body.

To renounce fleeting worldly concerns is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

This verse speaks of the need to renounce this ephemeral life. If we can't relinquish our worldly habits and pleasures while practicing the Dharma, they become significant hindrances on our spiritual journey. As such, truly practicing the Dharma requires a renunciation of this life.

Cultivating a mindset of renunciation calls for a profound contemplation of life's impermanence, which can be understood through these three key aspects:

1. The timing of death is uncertain – no one can truly foresee when their end will come.

2. The cause of death is uncertain – countless factors could potentially lead to our demise.

3. Death is the sole inevitable truth – it's a destiny that no one can escape.

Reflecting on our existence through these three perspectives allows us to grasp the transient nature of life and the inevitability of death.

Reflect upon our worldly possessions. Every tangible thing we gather is bound to be depleted – all accumulation will inevitably diminish. All our treasured relationships, be they friendships, family bonds, or other kinships, are fated to dissolve – every union will unavoidably lead to a parting. Life, in its natural course, always leads to death – every birth is destined to die. These are the truths repeatedly emphasized by the Buddha in his teachings. To us, this life is but a fleeting moment. Thus, by meditating on impermanence, we can foster a mindset of renunciation towards this life."

Next, reflect upon our worldly possessions. Every tangible thing we gather is bound to be depleted – all accumulation will inevitably diminish. All our treasured relationships, whether friendships, family bonds, or other kinships, are fated to dissolve – every union will unavoidably lead to a parting. Life, in its natural course, always leads to death – all birth destined to die. These are the truths repeatedly emphasized by the Buddha in his teachings. To us, this life is but transient. Thus, by meditating on impermanence, we can foster a mindset of renunciation towards this life.

Among the profound teachings bestowed by Lord Manjushri to Sakya Pandita Kunga Nyingpo, there's a renowned doctrine called "Parting from the Four Attachments", which states:

If one is attached to this life, they are not a true practitioner.

If one is attached to samsara, they lack renunciation.

If one is attached to their own self-interest, they have no bodhicitta.

If there is grasping, they do not possess the View.

It's important to strive to relinquish these four attachments. Specifically, the first principle explicitly declares that if one remains attached to this life, one cannot be regarded as a genuine practitioner.

Likewise, in the renowned "Four Dharmas of Gampopa”:

Grant your blessing so that my mind may turn towards the Dharma.

Grant your blessing so that Dharma may progress along the path.

Grant your blessing so that the path may dispel confusion.

Grant your blessing so that confusion may dawn as wisdom.

The essence of the first Dharma in Gampopa's teachings, 'May my mind turn towards the Dharma', is to encourage us to relinquish our attachment to this life. One way to aid us in this renunciation is to meditate on impermanence. By ceaselessly reflecting on the immutable truth of impermanence, our attachments to this life will gradually diminish, eventually enabling us to let go.

This meditation on impermanence primarily serves to highlight the transient nature of our current life, indicating its ultimate meaninglessness, thereby assisting us in letting go. How does it become meaningless? As the verse reveals, relationships we diligently maintain, such as those with family and friends, are destined to face separation when impermanence strikes. As a result, "long-accompanying friends and family will inevitably part" – no matter how much we resist, the inevitability of death forces us to let go. "Wealth and possessions, gathered with great effort, will be left behind" – we toil to build wealth, always dreaming of the day when we can fully enjoy it, yet impermanence may come before we get the chance, facing us with death. At that moment, we realize that all our efforts in accumulating these material goods bear no significance in the face of death.

How should we perceive our own bodies? We should consider them as temporary dwellings, akin to guesthouses. Everyone harbors a deep attachment to their body, endeavoring to keep it healthy, but the body is merely a transient residence for our consciousness. When the inevitability of death manifests, our consciousness will transition to another destination. Consequently, all our strivings in this life become insignificant in the face of death. This realization encourages us to relinquish our attachment to the transient pleasures of this life.

What is the purpose of our precious human life, complete with the Eight Leisures and Ten Endowments? Fundamentally, its purpose is to serve as a tool enabling us to practice the Dharma. Through the conduit of this human life, we can achieve spiritual evolution. While this is indeed beneficial, we should not develop any attachment to the body.

-

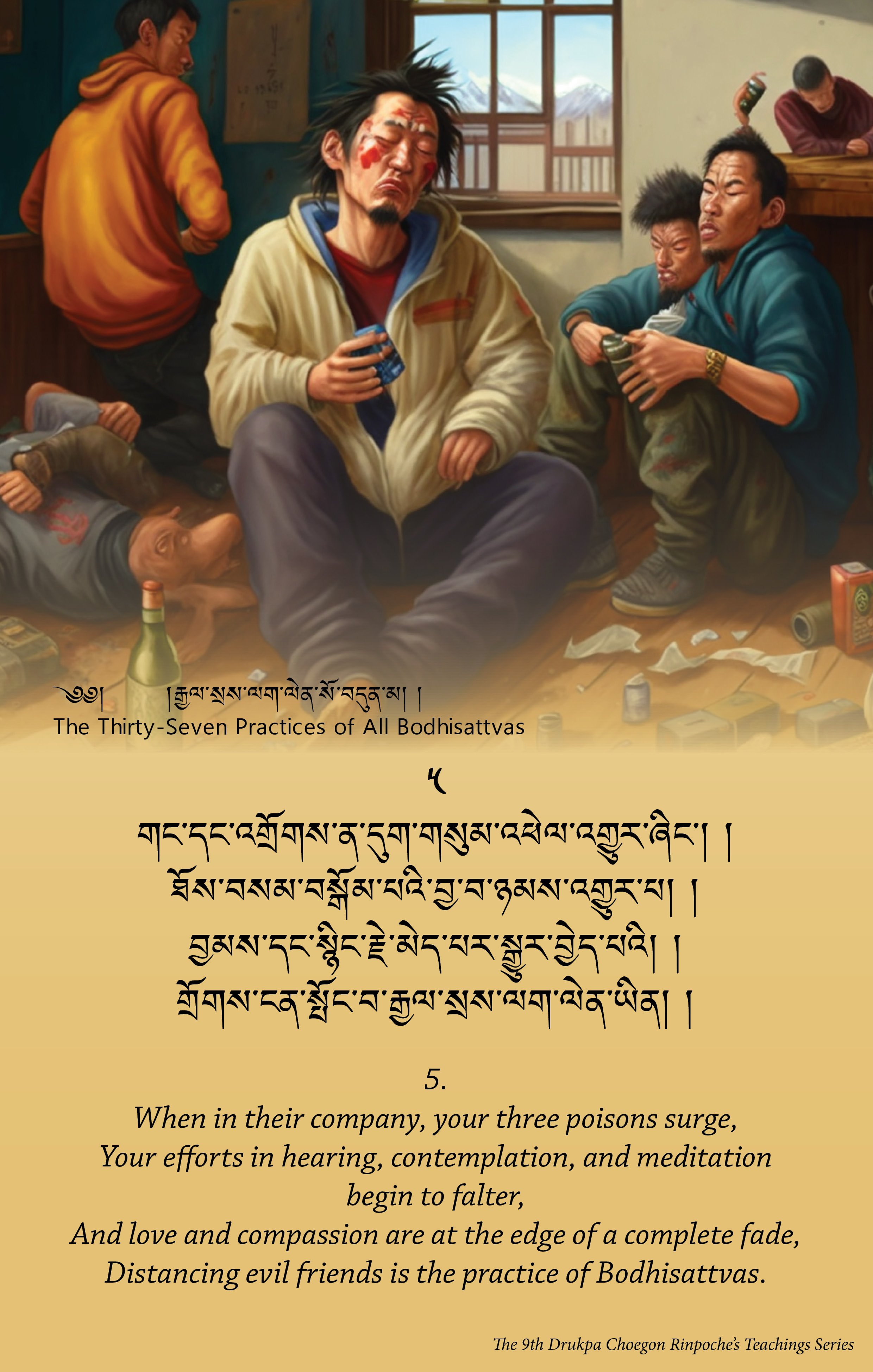

When in their company, your three poisons surge,

Your efforts in hearing, contemplation, and meditation begin to falter,

And love and compassion are at the edge of a complete fade,

Distancing evil friends is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

This verse underscores the importance of distancing oneself from harmful associations. Evil friends can be compared to patients infected with a highly contagious plague; when we encounter them, we instinctively strive to avoid them to prevent infection. Similarly, if we knew of a region known for its frequent visitation by dangerous animals, our immediate instinct would be to keep our distance. This mindset should likewise be applied when dealing with evil friends.

The teachings of the Kadampa highlight that harmful companions can exert a profoundly negative influence on us. An otherwise ordinary individual, when guided by a wise and virtuous mentor, could transform their negative tendencies under this mentor's influence and evolve into a good practitioner. Conversely, a virtuous practitioner persistently associating with harmful companions could find their accumulation of merit stalling, and over time, their existing merit may gradually diminish due to this negative influence, resulting in a progressive deterioration of their virtue.

To illustrate this, imagine a piece of white cloth. If it's placed next to a fire for a day, it might not show much change. However, if it stays there for a month, it would inevitably turn grey or even black. The influence of evil friends is similar. Encountering such individuals for a day or two might seem inconsequential, but over time, their impact can only worsen our moral character, hindering the growth of our spiritual merits.

As we traverse the path of spiritual growth, it is imperative to mindfully scrutinize our associations. When it comes to evil friends, we should sever the ties immediately, without the slightest hesitation.

-

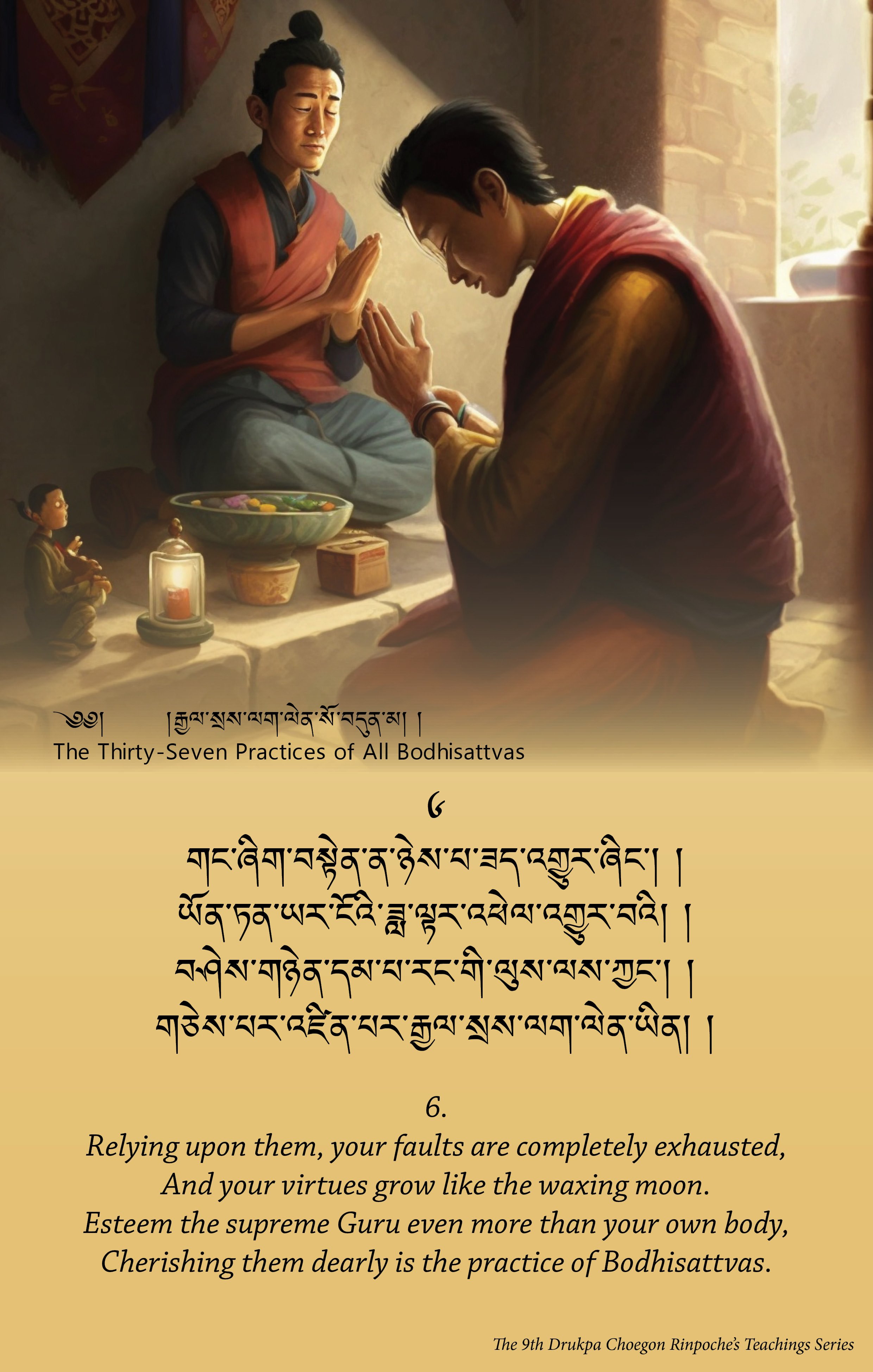

Relying upon them, your faults are completely exhausted,

And your virtues grow like the waxing moon.

Esteem the supreme Guru even more than your own body,

Cherishing them dearly is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

Relying on a virtuous spiritual mentor can lead to a significant enhancement of our meritorious deeds. As the Buddha declared, such reliance brings our inherent virtues into prominence, and under the mentor's guidance, new virtues previously unrealized start to gradually emerge. The mentor's guidance also helps in reducing our negative actions, thereby ensuring we do not fall into the three lower realms in the future. Moreover, this guidance continually sows seeds of virtue within our hearts.

The phrase, "Relying upon them, your faults are completely exhausted," implies that by relying on our Guru or virtuous spiritual mentor, we can gradually purify our past negative karma. As we abstain from negative actions, our virtues flourish, much like the waxing moon. With the virtuous mentor's constant guidance, our positive qualities continue to expand. Consequently, we should hold such invaluable mentors in even higher esteem than our own bodies. Cherishing such mentors nurtures our continuous growth in virtues. This is a fundamental practice of all Bodhisattvas.

In the context of Vajrayana, the virtuous mentor refers to the Guru who imparts the Tantrayana teachings. Conversely, in Sutrayana, the object of refuge is the ordained monks or Acharya. Whether it's the Guru in Vajrayana or the refuge master in Sutrayana, their teachings should guide our actions. We should strive to accomplish what our Guru or Acharya advises. With this mindset, we approach and rely on them, our virtuous mentors. Buddhist scriptures clearly state that during the degenerate age, the Buddha manifests in the form of Gurus or virtuous mentors to benefit sentient beings. Therefore, in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha, we should rely on these Gurus or virtuous mentors.

Recognizing that some people may not be able to attend teachings in person in the future, they have made an earnest request for oral transmission, enabling them to learn from recorded teachings later. However, oral transmission and teachings are two distinct things. Even after receiving the oral transmission, further guidance or instructions should still be sought. Ideally, one should receive oral transmission in person from the Guru, followed by direct, face-to-face instruction or guidance.

What does instruction mean in Tibetan Buddhism? It's a form of guidance, leading one toward a better state or place. For instance, when the great translator Marpa was instructing Milarepa, where was he guiding him? He was guiding him towards the fruition of the state of the union form of Vajradhara – the highest attainment in Vajrayana. Who was the guide? The esteemed Marpa Guru guided his disciple, Milarepa. How did he guide him? He did so through the skillful means of ripening empowerments and liberating instructions. Therefore, guidance holds paramount importance in the learning and practice of Dharma, particularly in Vajrayana.

-

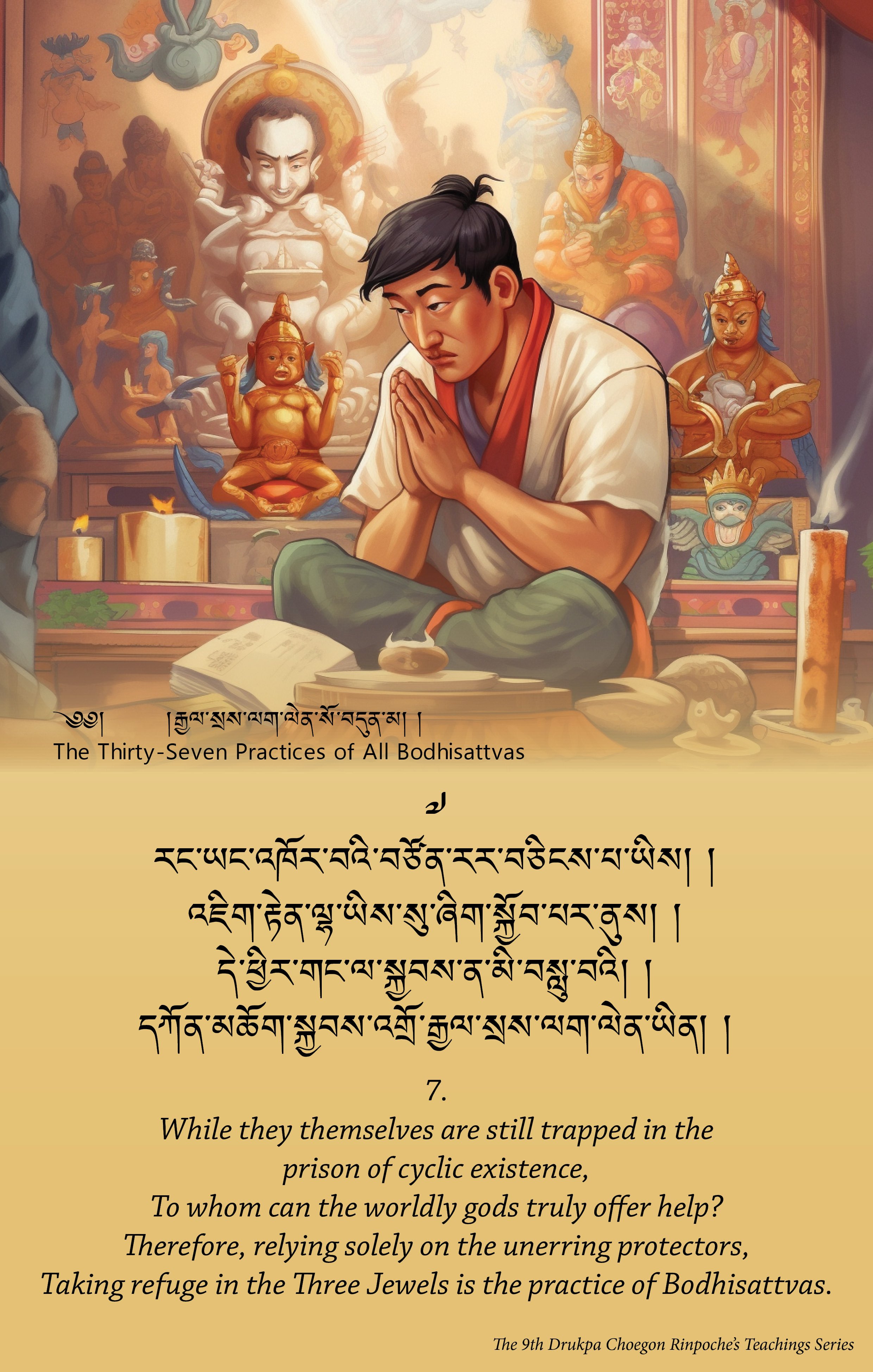

While they themselves are still trapped in the prison of cyclic existence,

To whom can the worldly gods truly offer help?

Therefore, relying solely on the undeceiving protectors,

Taking refuge in the Three Jewels is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

Now let's discuss the aspect of taking refuge. Taking refuge is an essential foundation of all Buddhist teachings. Without taking refuge before engaging in Dharma practice, we will not receive any precepts, and we will not embark on the path of practice. As the source of precepts is refuge, we must first take refuge, and then we can seek and uphold the precepts.

The Five Paths and Ten Bhumis that we traverse begin with taking refuge, and refuge is the foundation of all paths to Buddhahood. Therefore, without taking refuge, any form of practice cannot be considered as entering the “Path of Practice”. Thus, taking refuge is of utmost importance.

The distinction between Buddhism and non-Buddhist paths:

Furthermore, the primary difference between Buddhism and non-Buddhist paths is determined by taking refuge. We identify someone as a Buddhist because they have taken refuge. It is through taking refuge that we categorize ourselves as Buddhists. Thus, taking refuge is a crucial part at the outset of our learning of Buddhism.

When taking refuge, different people will have different objects of refuge. Some people take refuge in the mountain god, some in the water god, some in the worldly gods, some in the Naga King, or some people specifically worship a stone-made deity, which they regard as their reliance and object of refuge.

Why are there all kinds of objects of refuge? Due to ignorance, many people, not understanding the concept of refuge, pray to various entities. The Buddhist scriptures mention that when we are in pain, we may turn to divine beings like Naga Kings or deities for relief. However, in reality, these beings cannot completely eradicate our suffering. While they may provide a temporary respite from our pain, they are incapable of permanently freeing us from our suffering, and hence, are not our ultimate refuge.

The main reason for this is that these worldly deities or Naga Kings are themselves still trapped within the cycle of existence in the Three Realms, and they cannot even resolve their own suffering. Thus, they are incapable of liberating us from the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth, and cannot lead us to the complete cessation of suffering.

Taking refuge in the Three Jewels - the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha:

The only true object of refuge that can liberate us from the suffering of cyclic existence is the Three Jewels, i.e., the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. They are our sole reliance for refuge.

Let's start with a brief introduction to the Three Jewels. The Buddha does not possess the feelings of favoritism and discrimination that ordinary people have. The Buddha only has compassion for all sentient beings, without attachment or aversion. He continuously benefits all sentient beings with a compassionate heart. He does not differentiate by saying this one is a Buddhist, so I'll take special care of them, or this one is not a Buddhist, so I won't show them compassion. The Buddha has no such discrimination, instead, he shows universal compassion. The Buddha's ability to benefit all sentient beings without bias is one of his defining traits. Moreover, the Buddha possesses immense power, which is his ability to alleviate completely the suffering of Samsara. He is endowed with both mundane and transcendental virtues, the latter of which pertains to Nirvana. He is imbued with all the extraordinary virtues beyond this world.

Thus, such an entity, capable of continuously and impartially benefiting all sentient beings, possessing the power to transcend the pain of Samsara, and endowed with all the virtues of Nirvana, cannot be found in any other object of reliance, other than the Buddha. Therefore, when we seek an object of true reliance, even though Buddhists take refuge in the Three Jewels, the primary object of refuge is the Buddha.

When discussing the aspect of taking refuge, we can delve into its essence, distinctions, and benefits, among other aspects. But in simple terms, we take refuge in the Three Jewels: The Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

The Buddha Jewel refers to the inherent nature of the Buddha, who possesses the three kayas: The Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, and Nirmanakaya. The Buddha possesses ‘The Wisdom that Knows the Nature of All Phenomena’ and ‘The Wisdom that Knows the Multiplicity of Phenomena’. His wisdom is perfect, and he has the Dharmakaya for self-benefit and the Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya for the benefit of others.

The Dharma Jewel refers to the teachings expounded by the Buddha and the intentions within the Buddha's mind. This is the true Dharma. As mentioned before, it includes both the ‘Dharma of Realization’ – the realization of truth within the mind, and the ‘Dharma of Instruction’ – the teachings expressed through words. This is what we call the Dharma Jewel – The enlightenment in Buddha's mind and his guidance and teachings through words.

The Sangha Jewel refers to those who earnestly practice and follow the teachings proclaimed by the Buddha, adhering to his words and implementing them. The term 'Sangha' typically refers to the Noble Sangha, meaning those who have reached the state of enlightenment. In Mahayana Buddhism, this refers to attaining the Bhumis (reaching the level of a bodhisattva), and in Theravada Buddhism, it refers to achieving the Four Fruition (the Four Levels of Awakening). These are the individuals to whom we can turn for refuge.

As mentioned earlier, the real and only object of our refuge is the Buddha Jewel, which actually encompasses all Three Jewels - the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. The Buddha's body represents the Sangha Jewel; his teachings, the Dharma Jewel; and his mind, the Buddha Jewel, that is, the Buddha himself. Therefore, while we take refuge in the Three Jewels, they can all be embodied in the Buddha Jewel.

A Buddha, possessing such perfect virtues, surpasses any worldly deities. Therefore, in the Root Verse of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva, it is said: "While they themselves are still trapped in the prison of cyclic existence, to whom can the worldly gods truly offer help? Therefore, recognizing the truly exceptional and unerring refuge, taking refuge in the Three Jewels is the practice of Bodhisattvas." This tells us that a Buddha, as one who embodies perfect virtues, is entirely incomparable to worldly gods who themselves are still within the cycle of Samsara. Therefore, we must take refuge in the unerring Buddha, who embodied the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

The Buddha serves sentient beings in manifold ways, one of which is his manifestation as a spiritual teacher. Especially in the degenerate age, when sentient beings cannot see the Buddha in person, the Buddha will appear in the form of a spiritual teacher, guiding those disciples with a karmic connection towards the path to liberation and ultimate Buddhahood.

-

The Dharma is categorized into the Dharma of Instruction and the Dharma of Realization:

The teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha primarily divided into two categories: the “Dharma of Instruction” and the “Dharma of Realization”. The former pertains to the spoken teachings, while the latter involves the internal realizations. The Dharma of Realization refers to the ultimate truth, embodied by the Buddha, who possesses both 'Wisdom that Knows the Nature of All Phenomena' and 'The Wisdom that Knows the Multiplicity of Phenomena'. This signifies a complete understanding of the nature and characteristics of all phenomena. Furthermore, the innate wisdom that arises within a Bodhisattva during meditation also constitutes the Dharma of Realization.

The Dharma of Realization transcends language, thought, and all conventional explanations. It encapsulates the wisdom of the Buddha and denotes the ultimate truth, reflecting the true Dharma in its most authentic sense. This reality lies beyond descriptive, differentiative, or intellectual understanding. However, to engender the Dharma of Realization or the ultimate truth in our minds, the Buddha provided a variety of guidelines and instructions. These teachings, expressed in speech and text, are collectively termed the Buddha's Dharma of Instruction.

The Buddha's Dharma of Instruction consists of teachings directly articulated by the Buddha, teachings endorsed by the Buddha, and teachings blessed by the Buddha. The teachings spoken directly by the Buddha are his personal pronouncements; the teachings endorsed by the Buddha are those are those that were spoken by others and affirmed by him. The blessed teachings are delivered by disciples expressing the Buddha's intentions through his blessings. Collectively, they are referred to as the Buddha's words or scriptures (Sutra).

Commentaries, known as treatises (Shastra), elucidate the Buddha's teachings and are authored by past great masters and scholars. Therefore, the Dharma of Instruction encompasses two parts: the Buddha's words (Sutra) and the treatises (Shastra).

Considering both the Buddha's words and the treatises written by eminent past masters, the Buddha's words stand out for their profound depth and supreme exceptionality, devoid of any confusion. As they are the Buddha's own utterances, they present a comprehensive understanding of everything, making them supremely authentic. On the other hand, treatises authored by renowned past masters like Nagarjuna, Asanga, Candrakīrti, and others are unparalleled in their wisdom and insight.

The Three Necessary Conditions for Writing Treatises:

When discussing the authors of treatises, we can categorize them into two groups: those who are Bodhisattvas that have attained the stages (Bhumis) and those who have not yet attained this level of realization.

Great Bodhisattvas like Nagarjuna, who have perceived the ultimate truth of the nature of reality, naturally compose treatises of significant value. However, treatises authored by Bodhisattvas who have not reached the Bhumis also exist. The key distinction is between those who are still within the realm of ordinary beings and those who have ascended to the realm of holy beings.

Generally, there are three necessary conditions for authoring treatises. At the highest level, one must be able to personally perceive the emptiness of the nature of phenomena. If this is unattainable, the intermediate requirement is to personally perceive one's Yidam deity and obtain their permission. At the most basic level, one must have a thorough mastery of the five sciences. Authors must meet at least one of these conditions to compose a treatise.

The Buddha's words and treatises both hold immense value. The words of the Buddha are extraordinarily profound, as seen in the essential and deep content of the "Diamond Sutra" or the "Heart Sutra". When we are unable to understand the Buddha's intent directly, we can gain insight into the Buddha's words by studying the treatises written by esteemed masters.

Therefore, the core content we aim to comprehend is the teachings given by the Buddha. We learn the content and purpose of the Buddha's teachings through the explanation and elucidation in treatises.

What can truly Eliminate Suffering and Quell Disturbing Emotions is the True Dharma

Regardless of whether it is the Sutra or Shastra, the real Dharma needs to be understood in a particular light. But what exactly is the Dharma? The primary purpose of the Dharma is to eradicate all forms of suffering and pacify all sorts of afflictions and obstacles. Therefore, for practitioners, when they cultivate the Dharma, it should serve to pacify and eliminate their inner suffering and keep them away from afflictions. If the practice can achieve this goal, then we recognize it as the Dharma, or the true Dharma. However, if the practice only seems to intensify the suffering or if the afflictions become increasingly strong, then this cannot be considered Dharma.

As previously mentioned, within the Dharma, there are two categories: the Dharma of Instruction and the Dharma of Realisation. The content we are currently studying pertains to the Dharma of Instruction. Within this Dharma of Instruction, there are the teachings of the Buddha and the treatises of the great masters. The treatises are further divided into those written by the great Indian masters and those written by the great Tibetan masters. Currently, we are studying treatises written by Tibetan masters. There are many great masters in Tibet, and our present study focuses on the writings of Thogme Zangpo. His work discusses how a practitioner enters the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path and how they put the practices of a Bodhisattva into action. This is summarized into thirty-seven points, known as "The 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas."

-

External and Internal Refuge

Refuge in Buddhism can be divided into external refuge, internal refuge, and secret refuge. However, in "The 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas," the primary focus is on exoteric teachings, and therefore it doesn't delve into the detailed distinctions found in Vajrayana. Let's briefly discuss these aspects of refuge here.

External refuge refers to taking refuge in the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, which is a form of outward refuge.

Internal refuge, as expounded in Vajrayana, is taking refuge in the Three Roots: the Guru as the root of blessing, the Deity as the root of accomplishment, and Dakini and Dharmapala as the roots of activities. These form the objects of internal refuge.

Recognizing Our True Nature is Ultimate Reliance – The Secret Refuge

In practical terms, the refuge we often speak of is the act of seeking support when faced with pain and threats. In confronting the suffering of samsara, we seek the path of liberation and thus look towards the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha for guidance. However, the ultimate form of refuge – the secret refuge – arises when our mind recognizes its own nature, understands the principle of emptiness inherent in all phenomena, and embarks on a practice grounded in this understanding of emptiness. This enables us to attain a state of ease in all circumstances, and represents our actual, true reliance.

This ultimate reliance is not on an external guru or the Three Jewels but rather on realizing the inherent emptiness within our own mind. From a Vajrayana perspective, this refers to the recognition of our own nature and the wisdom that emerges upon reaching a Bhumi (stage of enlightenment). From the first Bhumi to the tenth, and ultimately to the eleventh Bhumi of Buddhahood, there is a progressive deepening in the understanding of emptiness. This forms the core of our reliance, the ultimate refuge. Therefore, in the secret refuge, we take refuge in the realization of our own nature in relation to emptiness.

Mahamudra talks about the recognition of our bare nature as our ultimate reliance. Dzogchen speaks about the mind: its essence is empty, its nature is luminous, and its ground is all-pervasive compassion. By realizing this union of emptiness and compassion within our own minds, we can attain liberation from all forms of suffering. Both teachings elucidate the Tathagatagarbha, the Buddha-nature that is inherently present within all sentient beings. By fully manifesting the merits of the Tathagatagarbha and actualizing them in practice, we realize what is known as the ultimate refuge, also referred to as the secret refuge.

The Most Exceptional Aspect of Taking Refuge in Buddha Compared to Other Religions

We say that we take refuge in Buddha and enter Buddhism because we understand the exceptional and perfect virtues of Buddha, and that Buddha is our ultimate reliance. However, if that's all there is to it, other religions also have similar assertions. They would also say that the entity they take refuge in and rely on is more exceptional and perfect than others. So, what exactly are the unique points and characteristics of the Buddha, our object of refuge and reliance?

Merely claiming superiority over other religions verbally is meaningless. The Buddha's teachings require us to understand and recognize them, then practice and gain benefits from them. Only then can we say that Buddhism is indeed exceptional and indeed our best reliance, the entity we solely rely on.

When compared with other religions, the distinguishing feature of Buddhism can be understood from the Four Seals of Dharma, which are:

1. All conditioned things are impermanent – everything is in a state of impermanence, it changes;

2. All tainted things bring suffering – everything in this world will ultimately perish, and their final result brings us pain;

3. All phenomena are devoid of self – all phenomena are empty and lack inherent existence;

4. Nirvana is peace – the ultimate liberation can be attained.

The Four Seals originate from the teachings expounded by the Buddha after realizing that the essence of all phenomena is emptiness.

Because everything is a manifestation of emptiness, all appearances of things are an embodiment of impermanence, and impermanence leads to suffering. However, its essence is devoid of self and lacks inherent existence, it is emptiness, and through realizing it, we can attain the peace of nirvana.

Therefore, all phenomena are manifestations of the content of emptiness. We need to recognize and understand it, then practice diligently to gain the benefit of eliminating suffering. The ability to attaining complete liberation from suffering is the distinct difference between our exceptional object of refuge and other religions, and also where Buddhism differs from other religions.

The Goodness of the Middle – II) Main Practices

The following main practice section is the essence of the journey, as it encompasses the core teachings of the Bodhisattva path. It entails the contemplation and cultivation of bodhicitta, the observance of the bodhisattva vows, and various aspects of learning and practice associated with the path of Bodhisattvas.

-

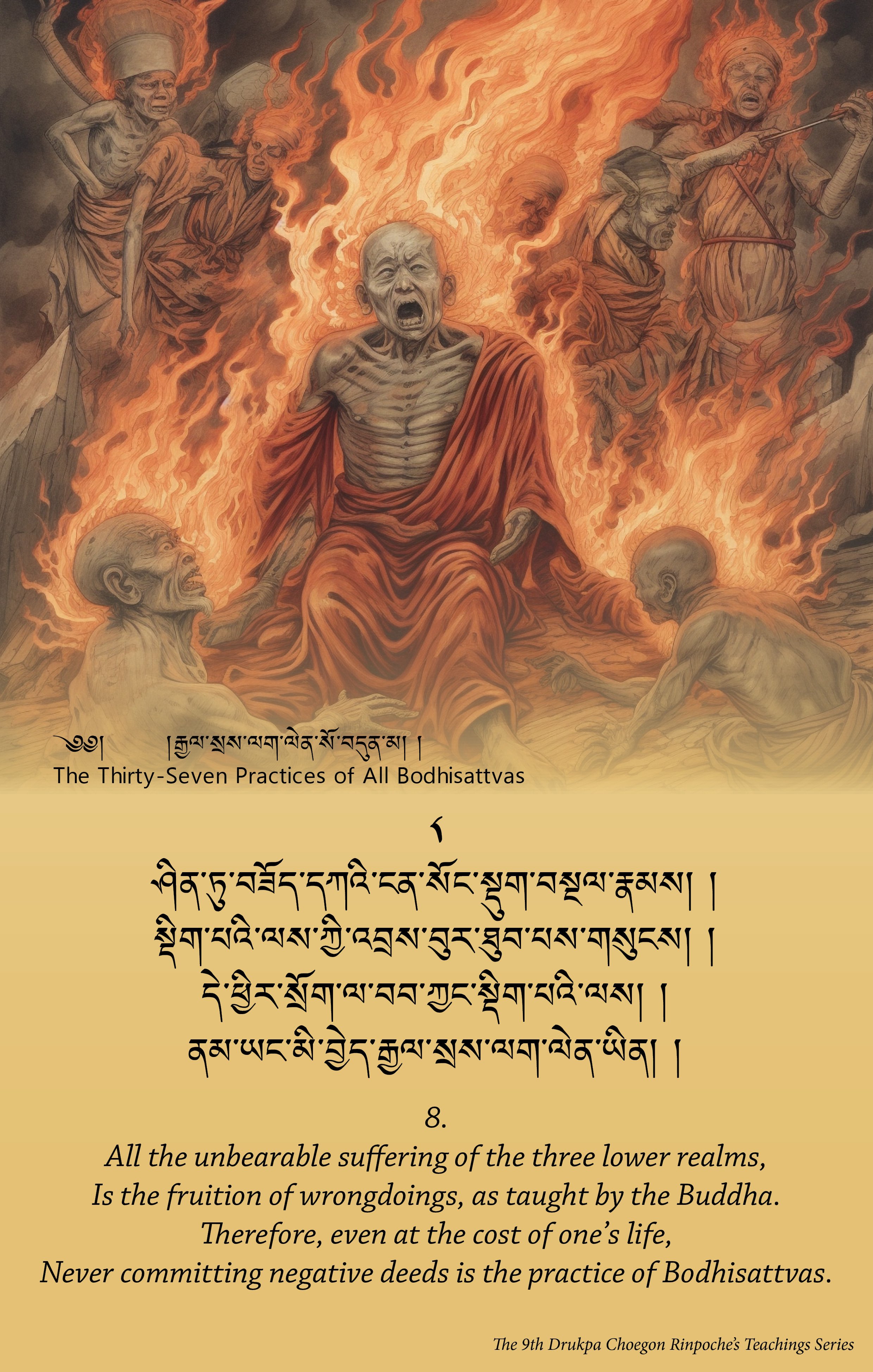

All the unbearable suffering of the three lower realms,

Is the fruition of wrongdoings, as taught by the Buddha.

Therefore, even at the cost of one’s life,

Never committing negative deeds, is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

Now, let us delve into the sequence of the path. First and foremost, we must cultivate a proper understanding of the worldly perspectives and make wise choices. Then, we embark on the path of liberation, known as the path of the Hearers and Solitary Realizers (Shravakas and Pratyekabuddhas). Subsequently, we progress towards the path of Mahayana, ultimately attaining the perfect fruition of Buddhahood. This is the order in which I will present the teachings.

The Ten Unwholesome Actions lead us to the Three Lower Realms

Let us first explore the correct understanding from a worldly perspective. It emphasizes that if we do not eliminate negative karma in our body, speech, and mind, and allow desires, anger, and ignorance to grow unchecked, we will engage in actions such as killing, stealing, and engaging in sexual misconduct with our bodies. Through our speech, we may propagate false speech, harsh speech, divisive speech, or frivolous speech. In our minds, harmful intentions, greed, and wrong views may arise. Ultimately, these actions will result in descending into the realms of hell, hungry ghosts, and animals.

Unwholesome actions of the body lead us to the realm of hungry ghosts, unwholesome actions of speech lead us to the animal realm, and unwholesome actions of the mind result in our own suffering and torment, driving us down into the realms of hell. Therefore, when we engage in these ten unwholesome actions through our body, speech, and mind, we are led to the Three Lower Realms, where we experience various forms of suffering.

How are the Three Lower Realms Created?

You may wonder how the realms of hell, hungry ghosts, and animals come into existence. Who is responsible for creating these confinements in hell for beings? In "The Way of Bodhisattva", it is stated that "the dungeons of hell and the guardians of hell are not created by other sentient beings, but rather, they form due to the collective karmic influence of sentient beings." This is the proclamation of the Buddha.

Even bodhisattvas who have attained the stage of enlightenment, let alone ordinary beings like us, lack the complete wisdom and omniscience of the Buddha. Therefore, we cannot fully comprehend the intricacies of cause and effect. However, the Buddha possesses complete insight into cause and effect and knows that all suffering originates from the negative karma created by sentient beings. Hence, the root verse states that the suffering in these unfortunate realms is the karmic result of negative actions.

Therefore, even when our lives are threatened, we should make a firm vow not to engage in such negative actions. In the Bodhisattva practice, from the perspective of worldly understanding, it is crucial to generate a strong commitment. From this moment onward, we must vow to eliminate the creation of negative karma and cultivate unwavering determination within us.

Everything Arises from Karma

In general, the world can be divided into two aspects: the world of phenomena – the environmental and physical surroundings, and the world of beings – all sentient beings existing within this environment.

Everything, both the world of phenomena and the world of beings arises from the force of karma. It is not created by anyone or any entity. Neither the world of beings nor the world of phenomena possesses inherent nature and substantial essence; they are devoid of inherent self-nature and ultimately do not exist.

In the Buddhist scriptures, it is mentioned that the same cup of water appears differently to different beings. To hungry ghosts, it may appear as pus and blood, while to beings in hell, it may appear as burning iron. In the human realm, it appears as water, and to celestial beings, it may appear as nectar. The perception of different manifestations of the same object is not due to the object itself being different but rather because the object itself lacks inherent self-nature. The varied appearances we perceive are a result of our own karmic forces, giving rise to different experiences.

Therefore, for sentient beings with heavy negative karma and intense attachment, aversion, and ignorance, the world they perceive is akin to hell. Thus, in "The Way of Bodhisattva," Lord Santideva proclaimed: "Who creates the burning red earth? From where do the hellish wardens come? Everything arises from the force of karma."

In summary, the experiences and manifestations in the world are dependent on the force of karma and the subjective perception of sentient beings. The world itself lacks inherent self-nature and is a product of the interplay of karmic forces.

It is better to Deeply Believe in Cause and Effect than to See the Yidam Deity in Person

The Buddha has taught that everything in the world of phenomena and beings arises from the force of karma.

Therefore, when we talk about the power of cause and effect, if we do not deeply believe in the principles of cause and effect, we will continue to engage in negative actions and consequently experience various forms of suffering.

Therefore, the great masters of the Kadampa have said, "It is better to deeply believe in cause and effect than to simply seek to physically see the deity." This means that even though we may have the opportunity to physically see the deity, if we lack faith in cause and effect and a profound understanding of it, we will continue to create various karmic actions and remain in a state of suffering.

Even if we physically see the deity, the force of karma will not cease because all suffering arises from the force of karma. The Kadampa masters believe that the true essence of the teachings proclaimed by the Buddha lies not in merely seeing a particular deity but in our genuine faith and understanding of cause and effect.

The key to our Dharma practice and the quality of our practice depends on how much importance we give to cause and effect. The more we value cause and effect, the more meticulous we become in our actions of body, speech, and mind, and the more complete our practice becomes. If we do not value cause and effect, our actions of body, speech, and mind will lack discipline, and our practice will be filled with various kinds of negligence and indulgence.

Therefore, in this verse, it is stated: "The Buddha has taught that the suffering in the lower realms is the karmic result of negative actions." This verse is a reminder for us to deeply believe in cause and effect and to give it the importance it deserves.

The Key to Excelling in the Yidam Practice lies in Our Reverence and Value for Cause and Effect

When we enter the realm of Buddhism, it is essential to cultivate a proper understanding of worldly perspectives, specifically a deep belief in cause and effect. If we don't value cause and effect, various obstacles will arise.

When we engage in the practice of Dharma without a profound belief in cause and effect, even if we perform the same practices, such as contemplating and cultivating devotion to the deity, reciting their mantras, and reflecting upon their teachings, we won't be able to achieve the same results as described by the Buddha.

Why is that? This is because of our lack of belief and importance given to cause and effect. For example, when practicing devotion to the deity, there are vows to uphold, and these vows are based upon the principles of cause and effect. If we don't value cause and effect, it becomes easy to violate these vows, leading to the emergence of various obstacles.

The concept of cause and effect explains that negative actions lead to suffering, while virtuous actions lead to happiness. If we disregard this concept and engage in reckless and careless behavior, we will experience obstacles and suffering in this life and be destined for the three lower realms in future lives.

It is because of our reverence, vigilance, and even fear of the karmic cause and effect that we become cautious in our actions and strive to avoid mistakes, aiming to walk the path of goodness. This allows us to practice well.

Therefore, even if we engage in the same Dharma practice, the same Yidam practice, some individuals excel while others struggle. The main difference lies in whether we have a sense of reverence and value for cause and effect.

Compared to Understanding Emptiness, developing a Deep Belief in Cause and Effect is more Remarkable

In Nagarjuna's "The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way," it is stated that "emptiness can be understood through our wisdom, but what is more difficult to attain is a deep belief in cause and effect."

When it comes to understanding emptiness, there are two ways: direct perception and logical analysis. Direct perception is when you directly realize emptiness, while logical analysis involves using your own thinking and reasoning to analyze and understand that all phenomena are empty in nature. This intellectual understanding of emptiness can also be obtained through rational thinking.

However, what is more challenging is to have a deep belief in cause and effect. Why is that? Because how can we attain complete enlightenment or liberation? The teachings of the Mahamudra state that we must have fervent devotion and earnest supplication to our spiritual teacher and accumulate spiritual merits. Through the convergence of these causes and conditions, we can attain realization. This convergence is, in fact, cause and effect. It is through cause and effect that we can achieve the liberation and enlightenment we aspire to. Therefore, if we do not value cause and effect, the desired results will not manifest.

Thus, in relation to the understanding of emptiness, whether it is Nagarjuna or Santideva, they both consider having a deep belief in cause and effect as something more difficult to attain and more remarkable.

There is a story of a practitioner who was in retreat, and a mouse entered the retreat room. Because he didn't want the mouse in the room, he deliberately killed it while reciting the Heart Sutra, contemplating the emptiness of all form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental phenomena, and their return to emptiness. However, this act of killing the mouse was indeed creating negative karma, and in the future, he will have to experience the corresponding negative consequences. Although he had some understanding of emptiness, his actions did not reflect a genuine appreciation for cause and effect.

Guru Rinpoche taught us that even if our view is as high as the sky, our actions should align with cause and effect. Therefore, when we study Dharma, instead of solely focusing on understanding emptiness, we should place greater emphasis on being cautious and mindful of cause and effect.

The verse "All suffering endured in the three lower realms is the fruition of wrongdoings" emphasizes the importance of cause and effect and urges us never to engage in negative actions, even in the face of difficult circumstances.

-

The pleasures of the three realms, like dewdrops on a blade of grass,

Vanish in an instant, gone within a blink.

The eternal, supreme state of liberation,

Striving for this is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

In the previous verse, we discussed the importance of deeply believing in cause and effect to avoid falling into the three lower realms. However, even if we are reborn in the higher realms, is it truly beneficial to aspire for the rewards of the human and celestial realms, to desire a powerful heavenly body, or to seek enticing worldly pleasures?

The Sufferings of Samsara

The world can be divided into three realms: The Desire Realm, The Form Realm, and The Formless Realm. Alternatively, we can perceive it as the Realms of Birth, Death, and the Bardo in-between, or as the Underground, Earthly, and Heavenly domains. In all these realms of existence, there is no such thing as true happiness.

The sufferings of samsara can be summarized into three types: the suffering of pain, the suffering of change, and the pervasive suffering. There is no place in the world where one can escape these three forms of suffering. As long as we are in these realms, we will inevitably experience one of these forms of suffering.

The Fleeting Momentary Happiness

This verse “The pleasures of the three realms, like dewdrops on a blade of grass" signifies that genuine happiness cannot be found in any realm of existence. Even if there seems to be a fleeting sense of joy, it is as fragile as a dewdrop on a grass tip. Ultimately, it does not represent true happiness, as everything is impermanent and subject to decay and destruction.

The primary message of this verse is to cultivate the aspiration to attain liberation from the cyclic nature of the three realms. It urges us to develop the mindset of renunciation, seeking complete freedom from the cycle of samsara.

What is renunciation?

We must understand that every aspect of worldly existence is inherently marked by suffering. Therefore, we should not cling to it but strive to liberate ourselves from this suffering. This is the essence of renunciation.

If we are attached to the world, we cannot truly cultivate renunciation. The renowned Sakya doctrine, "Parting from the Four Attachments," states that if we attach to samsara, we cannot be considered to have the mind of renunciation.

If we can constantly contemplate and develop the thought of seeking liberation from the cycle of the three realms, day and night, recognizing that samsara is like a fiery pit and desiring to escape from it as soon as possible, then these thoughts constitute genuine renunciation. This is the state of mind described by Master Tsongkhapa in "The Three Principal Aspects of the Path," where he emphasizes three essential paths: Renunciation, Bodhicitta, and Right View. These paths lead to liberation and enlightenment through the realization of emptiness.

Renunciation, Compassion and Bodhicitta

When we think about ourselves, it is the mind of renunciation.

When we think about others, it is the mind of great compassion.

The mind of renunciation arises when we contemplate our own situation and recognize the profound suffering of cyclic existence. We no longer wish to remain in this state but to be free from it swiftly, leading us to develop the mind of renunciation. On the other hand, when we think about others, we empathize with their suffering, and this gives rise to the mind of great compassion.

Having the mind of renunciation urges us to engage diligently in the practice of the Dharma, continuously cultivating the path. With the mind of great compassion, we aspire to alleviate the suffering of others, leading us to generate the mind of bodhicitta, aspiring to attain enlightenment for the benefit of others.

The Principles of Renunciation, Bodhicitta, and Wisdom are Consistent across all Lineages:

The teachings of renunciation and bodhicitta share common principles in the teachings of all esteemed masters across traditions. For example, in the Gelug tradition, these concepts are elucidated in "The Three Principal Aspects of the Path" by Master Tsongkhapa. The Sakya tradition also expounds similar principles through "Parting from the Four Attachments," where it is highlighted that attachment to this life hinders renunciation, self-centered motivation obstructs bodhicitta, and grasping and attachment to views distorts right view. These teachings correspond to the concepts of Renunciation, Bodhicitta, and Right View as presented in "The Three Principal Aspects of the Path" by Tsongkhapa.

The same principles are echoed in "The Four Dharmas of Gampopa," which urge us to turn our minds towards the Dharma, enter the path through the Dharma, eliminate confusion on the path, and transform confusion into wisdom. The first aspect, turning our mind towards the Dharma, reflects the renunciation of attachment to worldly pursuits.

Thus, the teachings of enlightened beings across traditions are consistent in their essence, sharing the same understanding and ultimate goal. They guide us toward liberation and the attainment of true and lasting happiness.

-

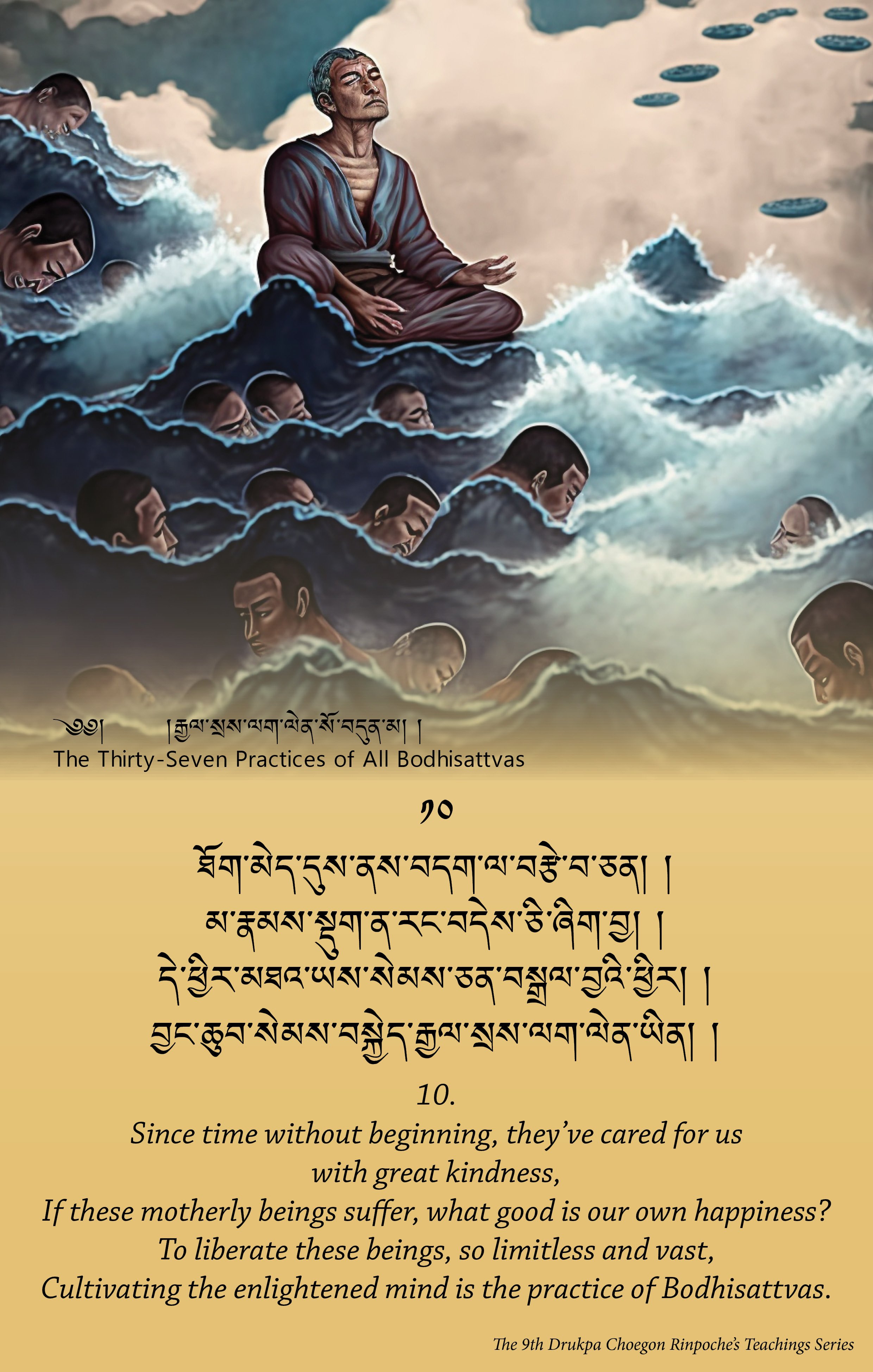

Since time without beginning, they've cared for us with great kindness,

If these motherly beings suffer, what good is our own happiness?

To liberate these beings, so limitless and vast,

Cultivating the enlightened mind is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

After discussing the mind of renunciation, we move on to the contemplation and cultivation of Bodhicitta, the mind of enlightenment. This verse teaches about the practice of Bodhicitta, structured into three stages.

The Three Stages of Bodhicitta Practice and Cultivation

First is the arousal of the extraordinary mind of Bodhicitta. This is the mindset we need to cultivate within ourselves.

Second comes the actual practice of Bodhicitta. This is referred to as ‘Action Bodhicitta’, as explained in the "Bodhisattva Caryavatara". It outlines how to practically implement Bodhicitta into action, how to manifest Bodhicitta in daily life, how to contemplate Bodhicitta, etc.

Third involves the study of Bodhicitta, namely, The Six Paramitas, which are the essential teachings to be internalized.

The "Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas" primarily focuses on Bodhicitta and the bodhisattva path, making Bodhicitta its main content.

Bodhicitta is the Union of Compassion and Wisdom

We often discuss the generation of a mind, but what kind of mindset should we cultivate? The process of arousing Bodhicitta involves two main aspects:

First is the aspiration to benefit others;

Second is the aspiration to achieve enlightenment.

Cultivating a mind for the benefit of others means to harbor a vast intention to benefit all sentient beings. This "other" refers to all sentient beings. And what is the ultimate correct practice that we need to undertake for this purpose? It is to aspire to attain perfect enlightenment. The perfect enlightenment here refers to the ultimate and complete Buddhahood.

The aspiration to benefit others involves cultivating a broad mind, which represents the great compassion in our hearts. The aspiration to achieve enlightenment concerns the ultimate wisdom we pursue. Therefore, the generation of Bodhicitta involves the union of compassion and wisdom. When discussing the cultivation of Bodhicitta, we need to remember that it involves these two key aspects.

What is great compassion?

When generating a mind to benefit others, the focus is on all sentient beings. The desire to benefit all sentient beings is an expression of great compassion. But what gives rise to great compassion?

As previously discussed, we possess the mind of renunciation when we contemplate the pervasive suffering inherent in the cycle of samsara, and find ourselves ceaselessly, day and night striving to escape this suffering.

Now, shifting our focus onto other sentient beings, what do we feel? All sentient beings desiring happiness, yet paradoxically engaging in inverted actions — committing various negative karmic deeds in their attempt to attain happiness. They yearn to avoid suffering, yet lack the wisdom to refrain from negative actions that beget the very suffering they seek to escape. Observing this jarring discrepancy between their behaviors and their innermost desires, we can't help but feel pity for them. The emergence of this thought, this feeling of profound pity for sentient beings trapped in their self-contradictory predicaments, this is what we call 'great compassion'.

All sentient beings have been our own mothers in countless past lives. When we generate the desire to repay their kindness, we touch upon the essence of great compassion, which is characterized by earnest wishes to benefit sentient beings.

There was once an elderly lady who asked a Kadampa geshe, "What is compassion?" The geshe, seemingly in a deep meditative state, said to her, "Ah, a pack of dogs is attacking your mother." The elderly woman, normally encumbered by physical disabilities and constant leg pain, momentarily forgot her pain upon hearing these words. She immediately stood up, fuelled by the urge to rescue her mother. At this moment, the geshe explained to her: "The mindset you possess right now, this urgent desire to save your mother - that is compassion!"

Such is the wisdom of the Kadampa teachings. Therefore, compassion is a state of mind where, upon reflecting on the suffering of other sentient beings, one overlooks one's own suffering and feels a compelling urge to assist others.

Compassion of the Mahayana vs. Theravada Traditions

Although practitioners of the Sravaka and Pratyekabuddha vehicles also possess the renunciation to liberate themselves from samsara, they do not exhibit the all-encompassing compassion for all sentient beings, a characteristic of the Mahayana tradition. While they certainly possess kindness and compassion for sentient beings, they do not hold the aspiration for all sentient beings to achieve liberation. This constitutes one of the main distinctions between the Mahayana and Theravada traditions.

The renunciation of the Theravada tradition is centered on self-liberation, while the renunciation of the Mahayana tradition prioritizes compassion for all sentient beings. This is why Bodhisattvas in the Mahayana tradition, through their cultivation of great compassion during practice, can manifest the courage to endure their own suffering and exert themselves in assisting others - as exemplified in the aforementioned scenario of forgetting one's own pain while rushing to aid a mother in distress."

Great Compassion is a Universal Remedy

The Buddha emphasized the vital importance of compassion throughout the scriptures, asserting that to attain Buddhahood, there is no need to master a multitude of dharma practices; learning just one is sufficient. And that singular, essential practice is the cultivation of great compassion.

Once we have developed renunciation, the key indicator that we are on the authentic path to Buddhahood is whether we have cultivated great compassion for all sentient beings. If we are able to generate great compassion for all sentient beings, then regardless how we walk the path, there will be no pitfalls; our course will invariably be correct.

Whether we practice tantra or meditate on a yidam, if we can envision the deity in person and harbor great compassion simultaneously, then our chosen path will present no hindrances; we will not veer onto other paths. Likewise, when practicing mindfulness of emptiness in exoteric Buddhism, irrespective of whether we can actualize the understanding of emptiness, if we let great compassion be our guiding light, we will not stray from our course.

For a practitioner imbued with great compassion, no adverse conditions or obstacles will obstruct their practice. The reason being, great compassion has the capacity to dispel all kinds of unfavorable conditions on the path. Just like a universal remedy capable of curing all diseases, great compassion holds the power to heal and clear all obstacles. As long as we possess great compassion, we will tread the correct path.

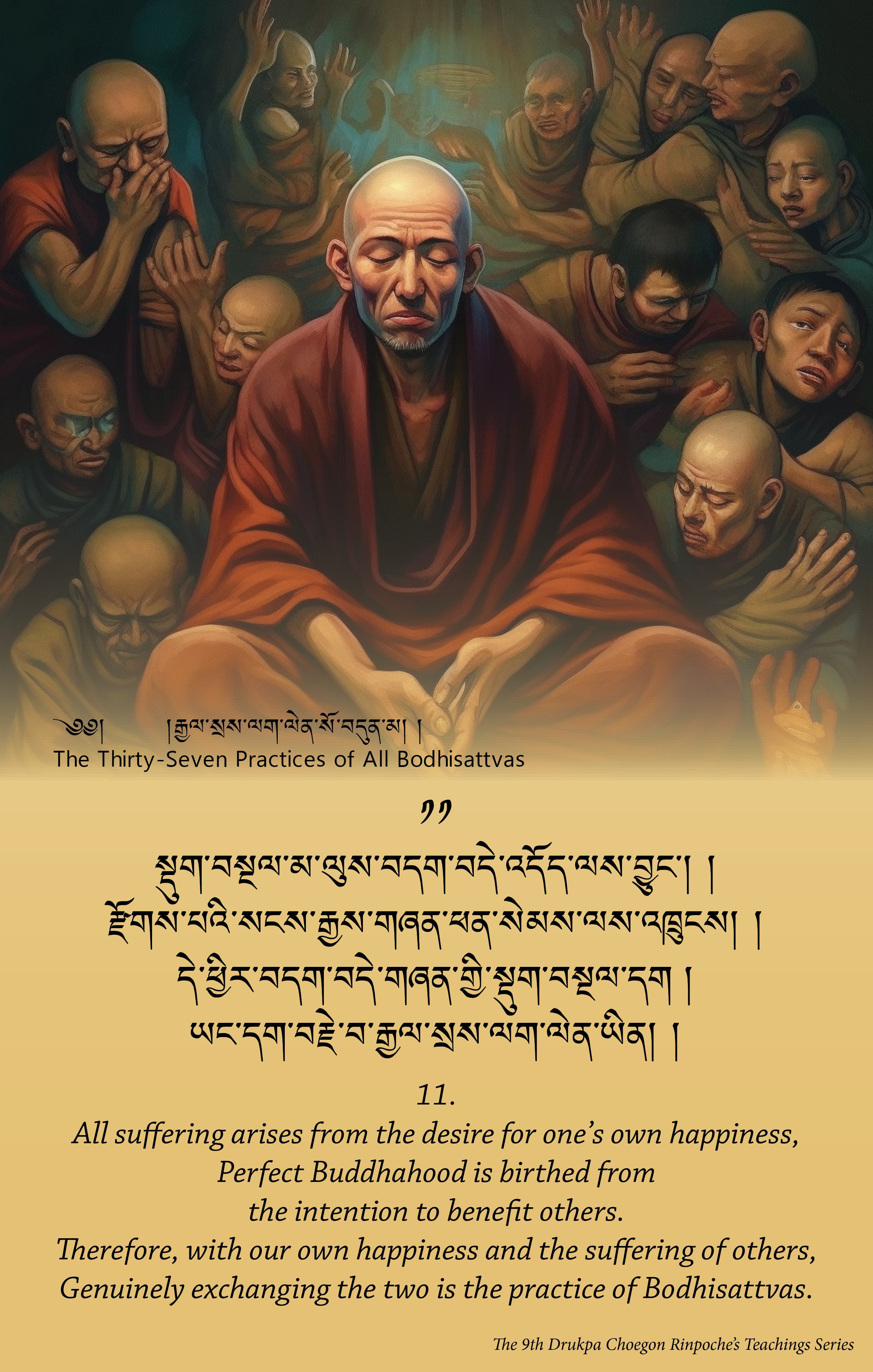

-

All suffering arises from the desire for one's own happiness,

Perfect Buddhahood is birthed from the intention to benefit others.

Therefore, with our own happiness and the suffering of others,

Genuinely exchanging the two is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

The previous verse touched on the generation of Bodhicitta. This verse delves into the practice of Bodhicitta. In the 'Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas,' the central teaching is the guidance on how to gradually progress from the cultivation of conventional Bodhicitta to the realization of ultimate Bodhicitta. Ultimate Bodhicitta is practiced through meditation, while conventional Bodhicitta is enacted through post-meditative activities in our daily actions – be they walking, standing, sitting, or lying down.

Our Incessant Suffering in Samsara Springs from Our Self-Interest:

To comprehend this verse, we start by contemplating: we have been self-serving through countless rebirths, which has resulted in our deep entanglement in the cycle of Samsara. In contrast, the Buddha, dedicated through countless rebirths to serving others and benefiting sentient beings, has broken free from Samsara and attained Perfect Buddhahood. Therefore, the root of our incessant suffering in Samsara is our self-interest, while the Buddha's liberation from Samsara and his attainment of Perfect Buddhahood, accompanied by everlasting peace and joy, is derived from benefiting others.

All pain stems from the self-serving desire for personal peace and happiness, whereas Perfect Buddhahood is achieved through benefiting others. Therefore, if we wish to achieve ultimate and everlasting peace and happiness, and to attain Perfect Buddhahood, it is crucial to engage in the practice of sharing our happiness with all sentient beings and bearing their sufferings. This practice of exchanging self and others is the fundamental practice of Bodhisattvas.

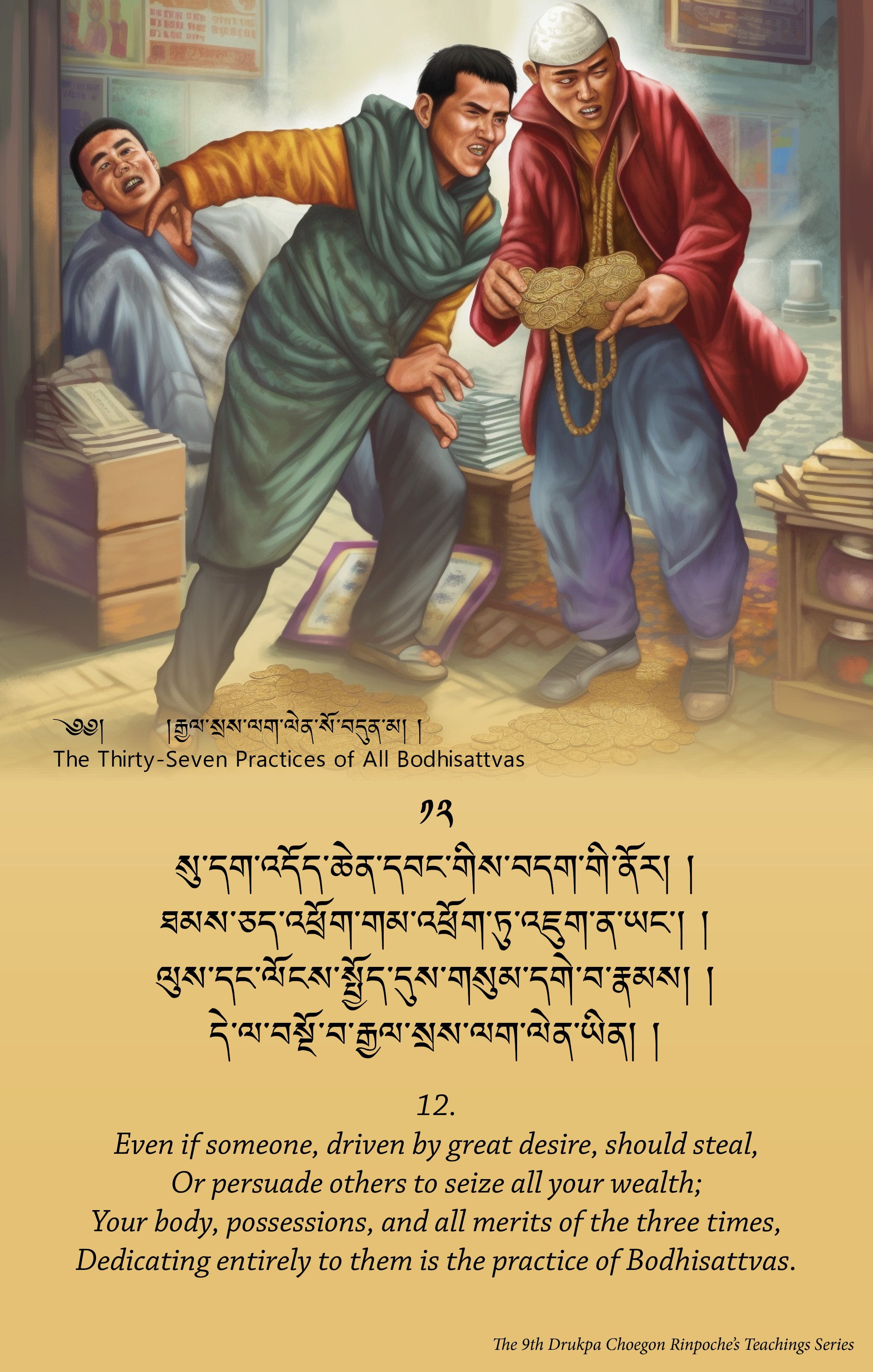

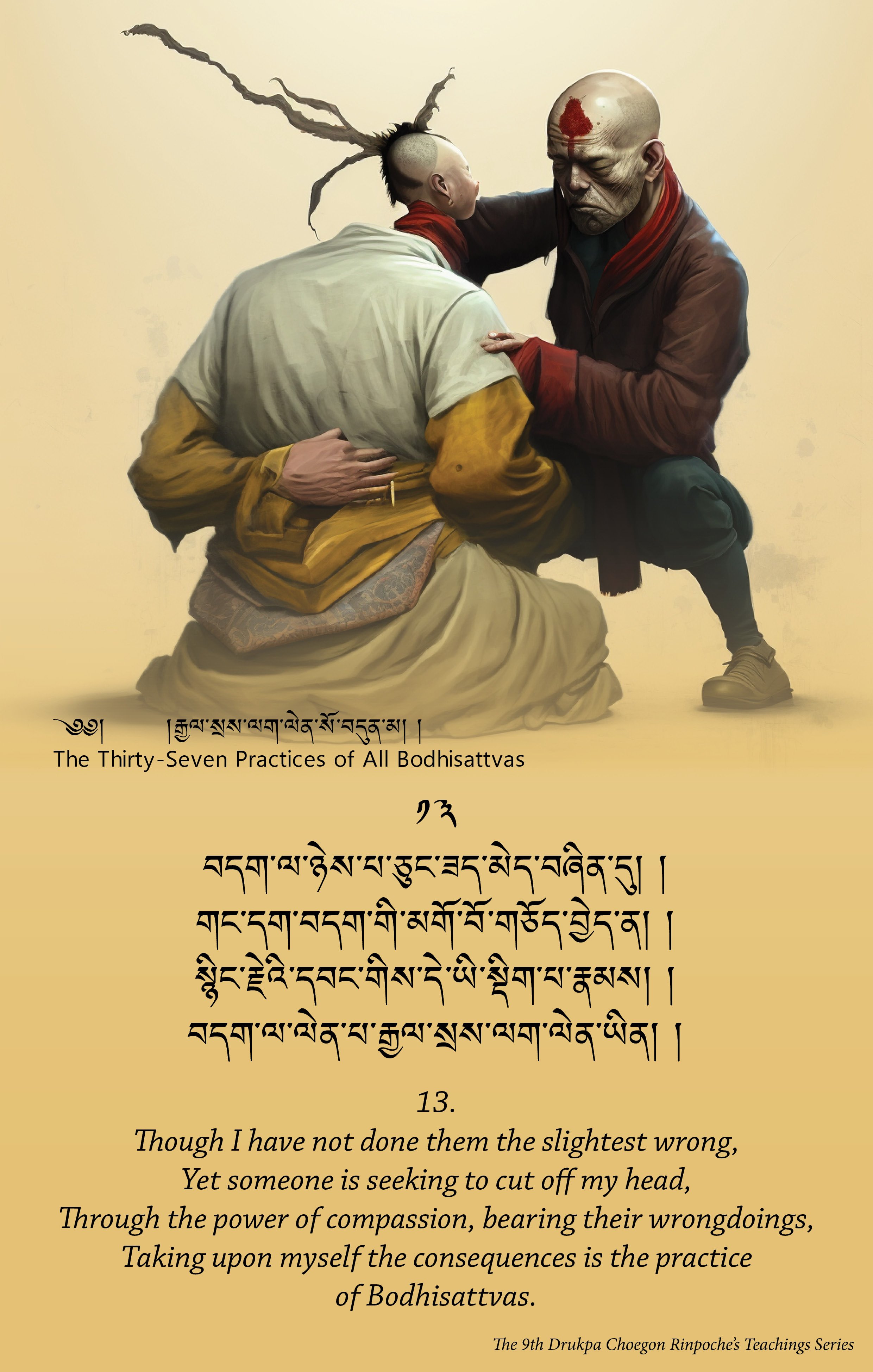

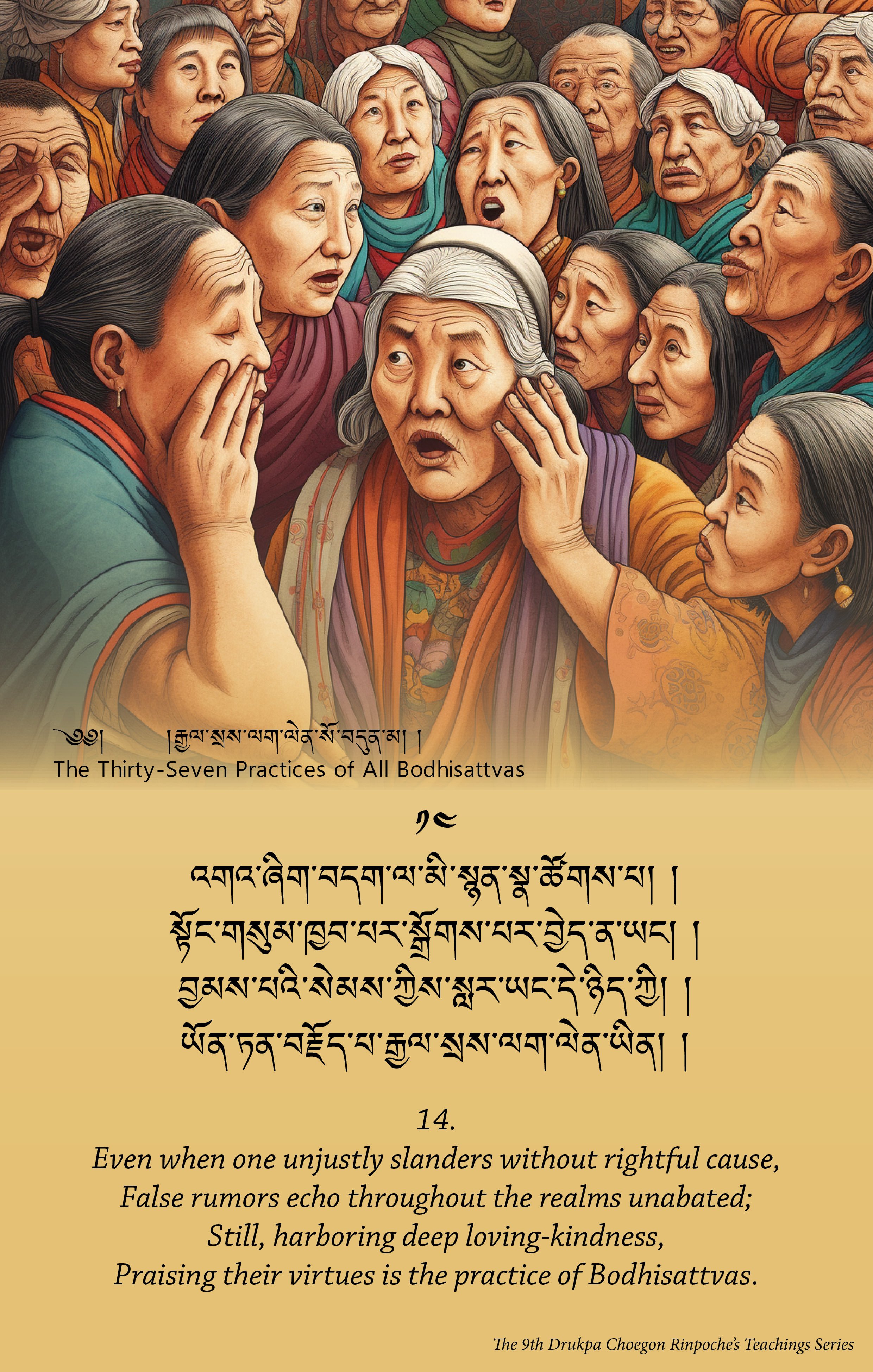

Contemplation of Ultimate Bodhicitta: